Introduction

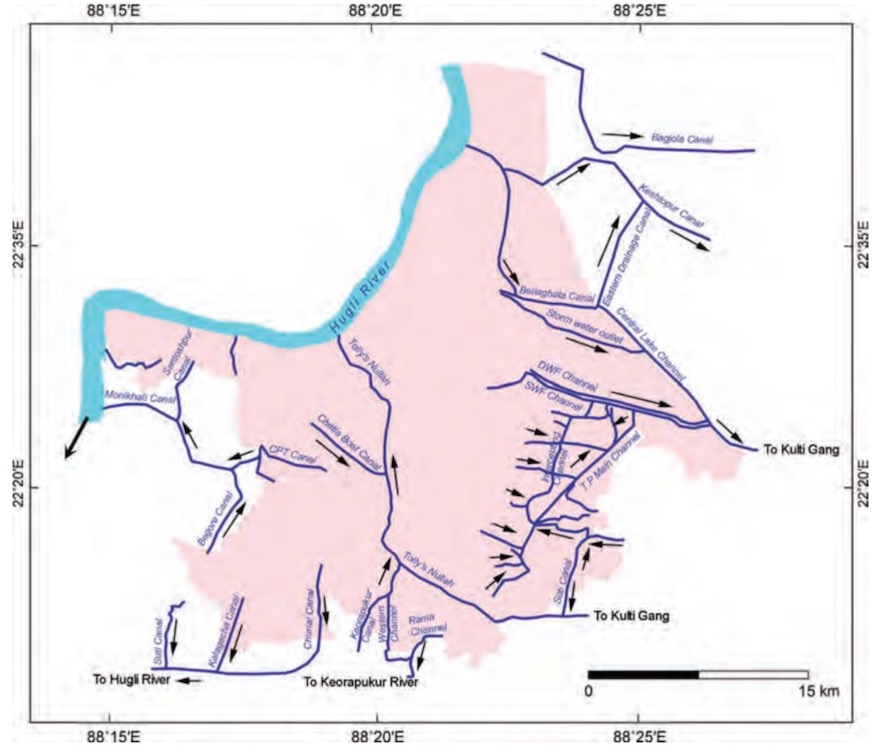

West Bengal has long enjoyed an elaborate river and canal system, even before the first colonizers arrived. The network reached almost every part of the state and historically served as the primary means of transport and trade. Upon their arrival, the British established their stronghold in Kolkata because of its advantageous location. With the Hooghly River on the west and the Bidyadhari River and saltwater lakes to the east, trade flourished. The East India Company laid out a series of canals over existing waters to make their latest colony profitable.

To put into perspective just how successful the canals were, between 1888 and 1889, the Eastern Canal system brought in Rs 4,22,000 in tolls, and Tolly’s Nullah alone made Rs 1,32,292 (Mukherjee 2020).

Over time, siltation caused the canals to deteriorate and the preferred method of transport moved to railways and roads. Empty canals soon became dumping yards for raw sewage.

The Early Days: Natural Canals of Calcutta

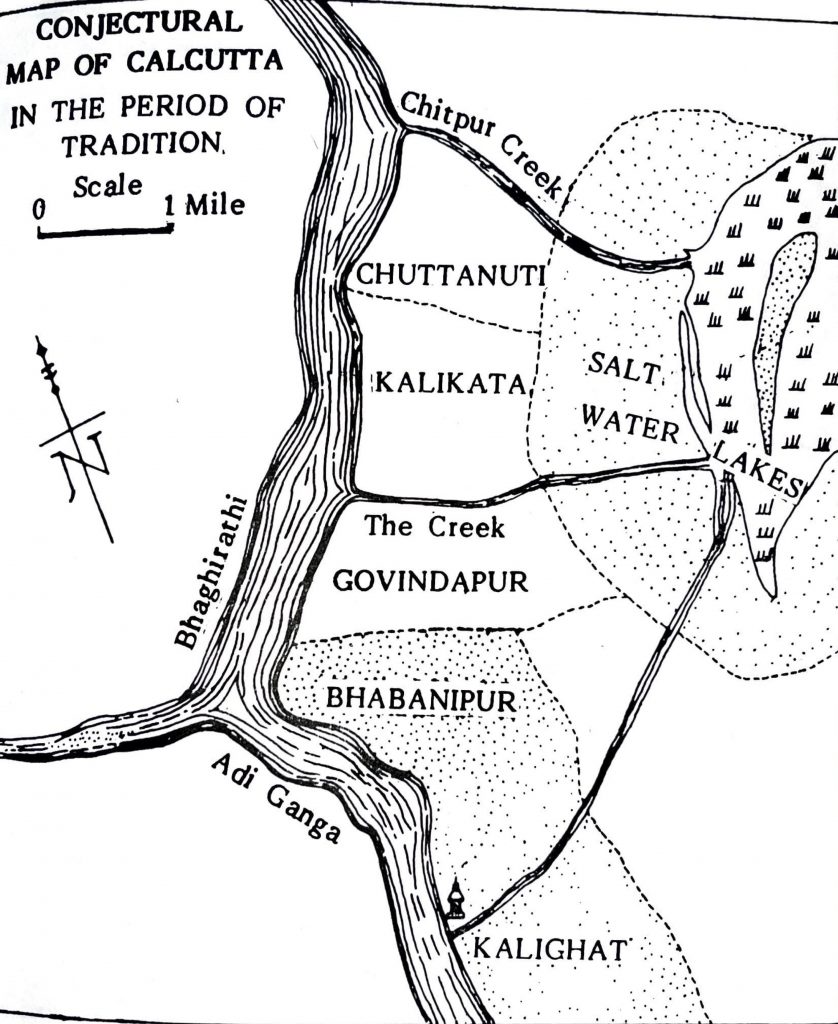

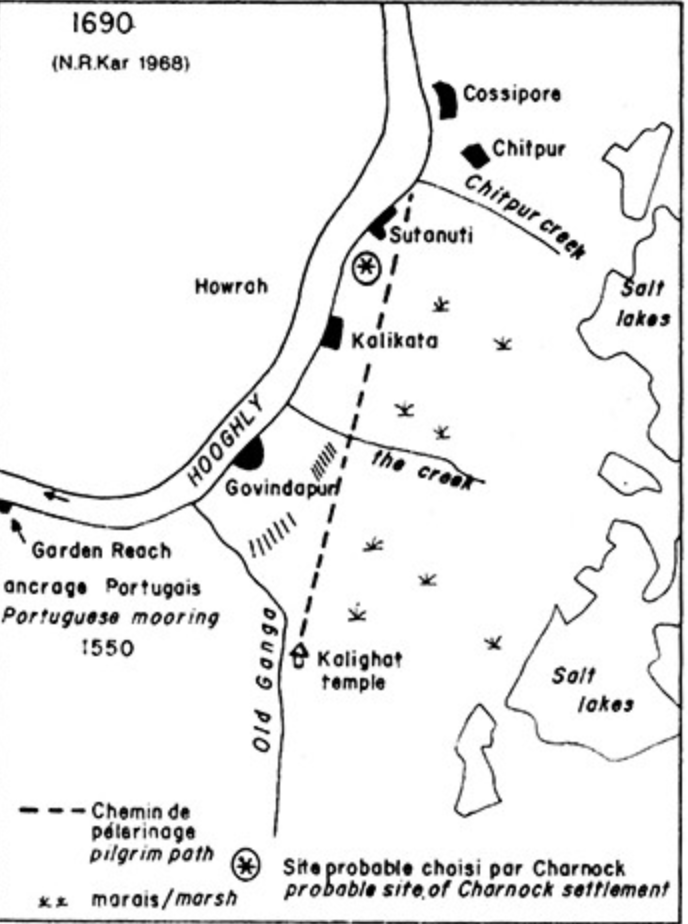

“There were two canals or creeks that separated Kalkata from Govindpur and from Sutanuti” (Biswas, 1992). “In its earliest days the sphere of influence of the English settlement extended for three miles in length, from the Chitpur Creek to the Govindapur Creek and about a mile in breadth, from the river Bhagirathi to the Chitpur Road” (Commissioner, 1902)

In the 17th century, Kolkata (or Calcutta as it was then known) comprised the villages of Sutanuti in the north, Dihi Kalikata, and Govindpur in the south. When the British first arrived, the settlement was a narrow strip of land. With the natural gradient spreading west to east and with cuts along banks of Hooghly (Kol–kata in Bengali translates to shores cut open), canals ran from west to east.

Chitpur Creek

Early maps (Munshi, 1990) show Chitpur Creek originating from present-day Baghbazar and flowing into the salt lakes. It ran along the northern boundary of the village of Sutanuti. In 1742, Mahratta Ditch, a deep trench, was constructed by the East India Company along this creek, and in the early 19th Century, the Circular Canal was excavated along the same route.

Creek separating Sutanuti from Kalikata

Oneil Biswas, author of the book Calcutta and Calcuttans from Dihi to Megalopolis, refers to two creeks forming a natural boundary around Kalikata (Biswas, 1992). Although maps do not reveal the existence of a creek between Kalikata and Sutanuti, the legacy of a creek could possibly be traced to the naming of Jorasanko, a neighborhood in Kolkata, (Jora-Sako meaning river bridge).

Calcutta Creek

Like its northern counterpart, Calcutta Creek existed along the southern boundary separating Kalikata from Govindpur. British historian Robert Orme referred to Calcutta Creek as a “deep murky gully”. The creek also had a bridge (sako in Bengali) that connected Kalikata with Govindpur in the South.

Calcutta Creek originated near Chandpal Ghat and flowed past today’s Kiran Shankar Roy Road (Hastings Street), Lenin Sarani, Wellington Square, Creek Row, Sealdah, Beliaghata, and finally into the saltwater lakes. In 1737, a catastrophic cyclone in Hooghly River caused a large ship to be carried from Hooghly River to Creek Row. This obstructed the creek’s flow and caused siltation which rang the death knell for Calcutta Creek.

Excavated Canals of Calcutta

Eastern Canal System

As the East India Company embarked on a colonial urbanization project in the city, they built over the existing framework of numerous canals and creeks that crisscrossed Kolkata and the rest of West Bengal. The complex system of interconnected rivers, canals, and lakes (including salt water) was combined with man-made ditches, excavations, pumping stations, lock gates, sluices, masonry sewers, and large-scale drainage and marsh reclamation projects.

| Name of the Canal | Year of Execution |

|---|---|

| Beleghata Canal | 1810 |

| Circular Canal | 1831 |

| New Cut Canal | 1859 |

| Bhangar Canal (canalised) | 1897 |

| Krishnapur Canal | 1910 |

| *Eastern Canal System and their excavation dates. Source: Mukherjee 2020 |

“The system performed the dual functions of trade-transportation and drainage-sewerage-sanitation, accomplishing the colonial economic logic of revenue extraction from inland navigation (connecting the city with its hinterland) and cost-effective delivery of urban utilities” (Mukherjee, 2020).

The “Circular and Eastern Canals” were the principal canals dug between the first decade of the nineteenth and the first decade of the twentieth centuries. The only 187-mile navigable path from Calcutta to Barishal was created by the excavation of the Eastern Canals. The Beleghata Canal, the Circular Canal, the New Cut Canal, the Bhangar Canal, and the Krishnapur (or Kestopur) Canal were the principal canals of the Eastern Canal System.

Tolly’s Nullah

In the 17th Century, the Adi Ganga River was the primary navigation route in the city and complemented the main riverine route of the Hooghly River. Adi Ganga’s banks near the neighborhood of Tollygunge were dotted with temples and bathing and cremation Ghats of which only a handful remain. In 1776, Major William Tolly excavated around eight miles of the Adi Ganga route from Hastings to Garia. Later, the canal was further excavated to meet the Bidyadhari River at Samookpota. In 1777, Tolly’s Nullah was opened to boat traffic. Even though Tolly’s Nullah lies outside the group of Eastern Canals, it was vital to the overall canal network.

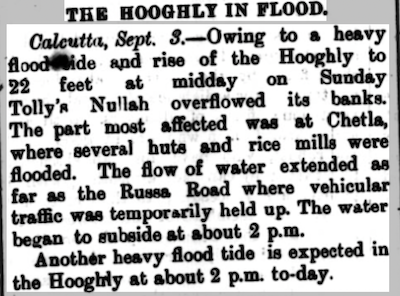

Currently, in large swathes of south Kolkata, Tolly’s Nullah, the almost entirely dry tributary of the Hooghly, regularly floods during high tide in the monsoons. The cause is the same as it was over a century ago i.e. the absence of sewage treatment plants and a constant discharge of effluents which raised the canal bed due to silt accumulation. Adding to the woes, illegal encroachments along the banks of the river continue to disrupt the flow.

The final nail in the coffin appears to have been the construction of 300 pillars supporting the Metro Rail extension from Tollygunge to Garia. There was a public outcry and a PIL (Public Interest Litigation) was filed in the High Court but Metro Rail resorted to using a 100-year-old norm that grants absolute authority to a railway project.

Beleghata Canal

Beleghata Canal was excavated between 1806-10 to improve upon an old channel running out from the salt water lakes. This canal, in its initial days, was not connected to Hooghly but functioned as a navigation route till 1947. Families that have lived on the banks of the canal for generations talk about it being an active route, bringing rice, fish, timber, vegetables, bamboo, and other commodities from the Barishal and Khulna districts in Pakistan via the Ichamati River route.

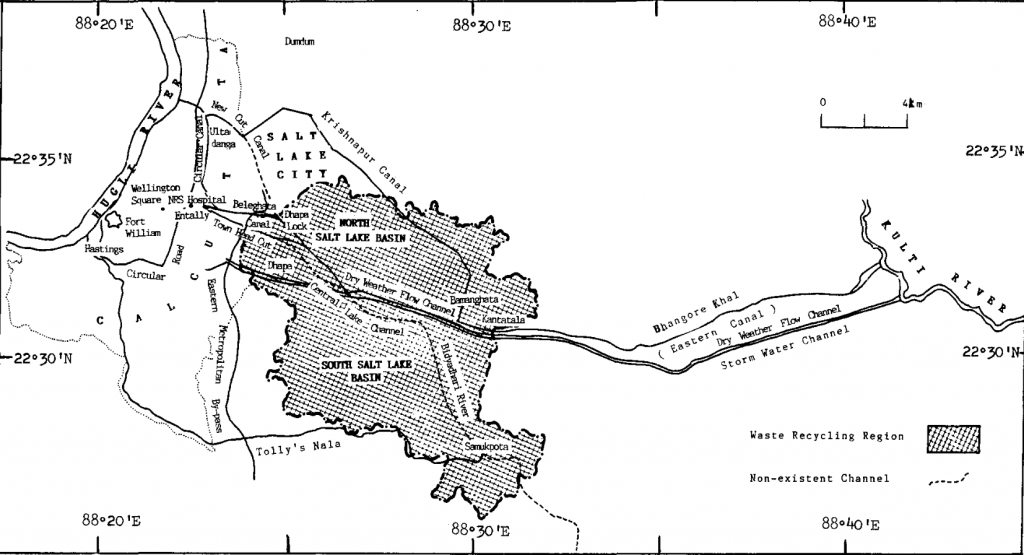

Circular Canal

The Circular Canal was opened for traffic in 1833, and with the completion of Chitpur Lock and its connection to the Hooghly, the boat traffic increased manifold. Chitpur Lock Gates were built to regulate the stormwater and effluent in the Circular Canal but the government found it quite difficult to balance the act of both draining the stormwater and navigation (of boats) through the Circular Canal. Currently, the Baghbazar system is initiated at the Chitpur lock in the Hooghly River, approximately two km inland, where it divides into the Circular Canal and Krishnapur (Kestopur) Canal. The circular canal is fed by effluent from the unsewered areas of Beleghata and Manicktala. It then travels approximately 12 kilometers to the southeast, where it again meets Kestopur Canal.

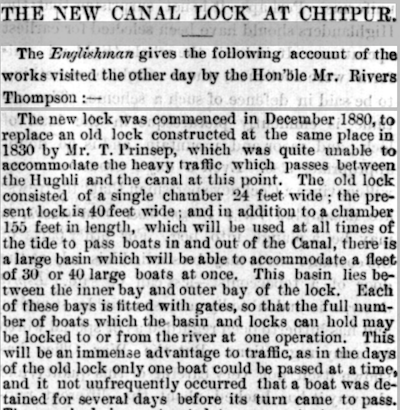

By 1880, with increasing traffic and trade demands via waterways, it became necessary to construct new lock gates at Chitpur to regulate the heavy boat traffic on the Circular Canal.

Here’s a news snippet reported by an Englishman in July 1882 detailing the construction of new lock gates.

New Cut Canal

In 1859, a new canal was excavated to connect the prior circular canal. Near Dhapa, it intersected with the Beliaghata Canal. However, The E.M. Bypass was constructed by filling up the segment of this canal from Ultadanga to Chingrighata.

Central Lake Channel

This ran through the saltwater lakes for six miles from Dhapa to Bamanghata where it merged with the Bidhyadhari River and then traveled 15 miles to meet Tolly’s Nullah at Samookpota.

Krishnapur (Kestopur) Canal

Krishnapur (Kestopur) Canal was cut in 1910 at an estimated cost of 910,014 rupees (Mukherjee 2020). This canal started from New Cut Canal, joined the Bamanghata-Kulti Canal, and finally joined Paran Chaprasir Khal connected to saltwater lakes. Today it is one of the major canals carrying sewage of North and East Kolkata

A portion of Kestopur Canal, today runs between Kestopur and Salt Lake. A footbridge and wooden bridge connect these areas over the canal.

Bidyadhari River & Kulti River Outfall Scheme

When the natural declivity of Kolkata was discovered to be on the east at the beginning of the 19th century, the Bidyadhari River was designated as the primary outfall channel for the city’s stormwater and effluent disposal. The river has since exhibited significant signs of deterioration and decay. This is the result of a combination of natural factors and a series of interventions it has confronted, such as the excavation and re-excavation of canals and cuts, and the reclamation of saltwater lakes.

As the Bidyadhari started to dry-up, due to a series of canalization initiatives, it could no longer be used as an outfall system of canals carrying the sewage/drainage of the city. As an alternative, the Kulti River was being used as an outfall scheme. The Kulti Outfall Scheme was developed per the plan submitted by Dr. B.N Dey, Chief Engineer, Calcutta Corporation in the 1930s.

Now, the Kestopur Canal, Bhangor Canal, Storm Water Flow Channel, and Dry Weather Flow Channel empty into the Kulti River near Ghusighata in North 24 Parganas. Thus, the effluents and stormwater from Kolkata are carried to the Kulti River and finally to the Bay of Bengal.

Major events related to canalisation in Calcutta

1777 – The excavation of Tolly’s Nullah, an old bed of the River Ganges, connected the Tolly’s Nala to the Hooghly River near Hastings and the Bidyadhari near Samukpota, causing siltation in the lower reaches of Bidyadhari.

1810 – Excavation of the Beleghata Canal. This Canal was an old channel through the Saltwater Lakes and was further extended westwards into the city.

1829 – Excavation of Circular Canal from Entally to Hooghly river leading to Rapid silting in the head end of the Central Lake Channel at Beleghata, which was the only drainage channel of the city. This was due to the creation of a tidal meeting ground of the Matla and the Hugli Rivers.

1830-34 – Excavation of Bhangor Khal leading to disturbance of tidal equilibrium of the spill-channels of the Bidyadhari and Kulti rivers

1859 – Excavation of New Cut Canal, leading from Ultadanga to Beleghata Canal and contributing to keeping up the level of water in the subsoil and interfering with drainage

1865 – A square mile area in the Salt Lakes was acquired and handed over to the municipal authorities for dumping of the city’s garbage, and for sewage farming and fisheries.This marked the beginning of land fills in the Salt Lakes

1897-98 – Canalisation of the Bhangor Khal and construction of the Bamanghata Lock to facilitate inland navigation leading to the deterioration of Central Lake Channel. Around 1900, salt water fisheries existed in the Salt Lakes. In 1904, a warning was given regarding alarming deterioration of the Bidyadhari river

1910 – Construction of the Krishnapur Canal—a shorter route joining the New Cut Canal with the Bhangore Khal. As a result more than 78 sq. km of the spill area of the Bidyadhari River was cut off. In 1913 a second warning was given but in 1928 the Bidyadhari River was officially declared as dead by the Government of Bengal. During 1930, first sewage-fed fisheries started and proved successful.

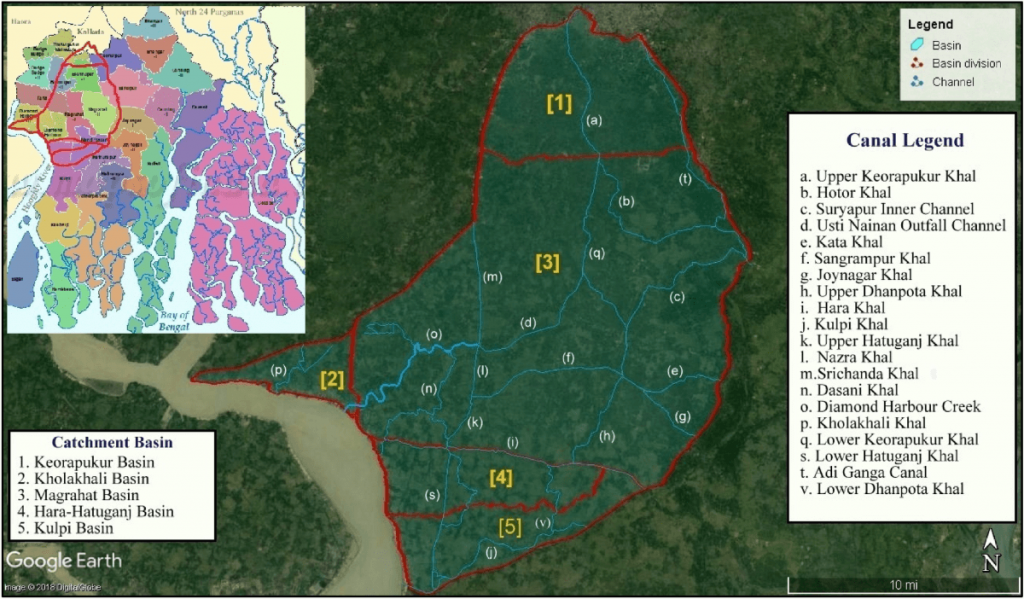

Keorapukur Canal

Keorapukur Canal branches off from Tolly’s Nullah near Purba Putiary, Kudghat, and continues southwards along M.G Road, Nepalgunj-Julpia Road to Magrahat. It is considered a tributary of Tolly’s Nullah. Keorapukur Canal in South 24 Parganas was a vital trade route in the 19th Century.

During the 19th century, Protestant missionaries used the Keorapukur Canal to navigate and spread Christianity. Rev. James Long, who is immortalized in the James Long Sarani that runs parallel to Diamond Harbour Road in Behala, was a prominent name amongst missionaries. The missionaries used dugouts like Salti to navigate the inland waterways and canals. Even today, the dominant presence of Churches, Christian Burial Grounds, and Convent Schools corroborate this fact.

Nepalgunje, in this road ahead, is still known for its rich agricultural produce. Back in the 19th century, it was through the Keorapukur Canal and Salti that fresh vegetables from around the country reached Calcutta. Even today, a fair share of vegetables in the Behala markets gets their supply from Nepalgunje, albeit by road. Keorapukur Canal is a feeder of Tolly’s Nullah which joins it in Kudghat through sluice gates. As the years have progressed, a once principal navigation route has been reduced to a storm/drainage channel.

Boat Canal

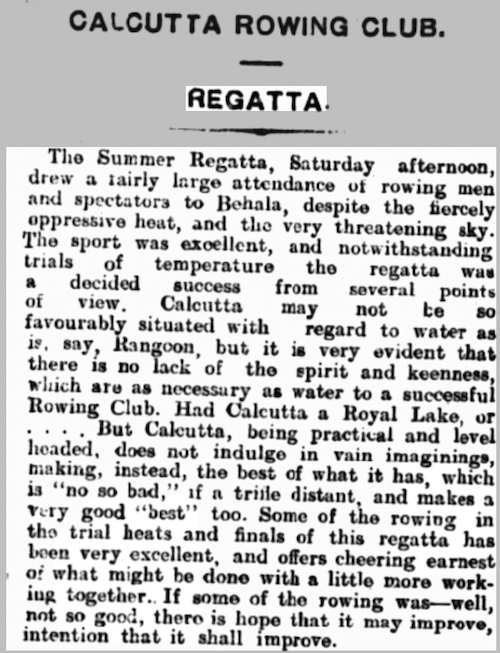

The Englishman’s Overland Mail on 21st July 1910 reported that “The Summer Regatta, Saturday afternoon, drew a fairly large attendance of rowing men and spectators to Behala.” Regatta is a sporting event consisting of a series of boat or yacht races. During 1910, this sporting event was held at the Boat Canal. The canal originally ran from Kidderpore Docks and met Tolly’s Nullah at Chetla.

The primary utility of this canal was to keep the water level at the docks high and to facilitate trade at the Chetla rice mills. The same canal was used for boat races or regattas organized by the Calcutta Rowing Club (CRC). Incidentally, CRC is among the oldest sports clubs in India. In the 1910s, CRC’s main site was at Behala and boat races were held at Behala’s Boat Canal until the club moved to Dhakuria.

Churial Canal

We find references to Churial drainage works in administrative reports from as early as 1928 (Report on the Administration of Bengal, 1928). The Churial Canal was originally a tidal channel which was later modified as a sluice-controlled drainage channel.

Manikhali Basin, Manikhali Canal, and their branch channels were included in the jurisdiction of KMC when it expanded in 1983 to encompass divisions from the municipalities of South Suburban, Garden Reach, and Jadavpur. Today, the drainage needs of nearly 66km2 within KMC and neighboring municipalities such as Maheshtala and Rajpur-Sonarpur are met by Churial Canal and Manikhali Canal, in addition to Tolly’s Nullah (Mukherjee, 2020).

“This scheme provides for drainage of Churial Basin comprising 39.81 sq. miles of rural area, 6.53 sq. miles of Behala Municipality area, 3.16 sq. miles of Budge Budge Municipal area. About 340 acres of land will be fully benefitted”, stated by the third Five Year Plan by West Bengal published in 1962 reports on the Churial Basin Drainage Scheme in the district of 24 Parganas.

By the 19th century, Calcutta’s canals—once the arteries of environmentally friendly transport—had become the primary means of flushing out storm water and wastewater from the city by gravity drainage. Pumping stations and sluice gates soon followed, establishing the city’s modern drainage infrastructure on the excavated and natural canal system. With ever-increasing population, man-made encroachments, siltation, reclaiming of wetlands, and unregulated urban development works, the canals are in constant threat. Most of these canals’ beds have significantly increased due to siltation, which is unable to hold stormwater, causing the city to drown during monsoons. Authorities, however, are gearing up for projects to dredge the silted canals and set up sewage treatment plants. Potentially, the best way forward is to develop an inclusive plan that is devised collectively by the local government, scientists and water experts, and the local communities. This ensures a sustainable roadmap to rejuvenate the deteriorating canals.

References

- Bandyopadhyay, S. (1996). Location of the Adi Ganga palaeochannel, South 24 Parganas, West Bengal: a review. Geographical Review of India, 58(2), 93-109.

- Biswas, A. R. (1992). Calcutta and Calcuttans, from Dihi to Megalopolis.

- Chatterjee, A. (2017). Genealogies of Sports Associations in Bengal: Historicizing the Institutionalization of European Clubs with Native Akharas. In Mapping the Path to Maturity (pp. 121-136). Routledge.

- Commissioner, I. C. (1902). Census of India, 1901: Calcutta (4 v.).

- Das, B. C., Ghosh, S., Islam, A., & Roy, S. (Eds.). (2020). Anthropogeomorphology of Bhagirathi-Hooghly river system in India. CRC Press.

- Ghosh, D., & Sen, S. (1987). Ecological history of Calcutta’s wetland conversion. Environmental conservation, 14(3), 219-226.

- Haraprasad, C. (1990). From Marsh To Township East Of Calcutta.

- Munsi, S. K. (1990). 2. Genesis of the Metropolis. In J. Racine (Ed.), Calcutta 1981 (1–). Institut Français de Pondichéry

- Mukherjee, J. (2020). Blue infrastructures. Singapore: Springer Singapore.

- Mukherjee, P., Das, S., & Mazumdar, A. (2021). Introducing winter rice cropping by using non-saline tidal water influx in western basins of South 24 Parganas, India. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 553.