Kolkata—the former capital of British India—boasts a plethora of historic monuments and landmarks which reflect its rich and diverse heritage. Dating back to the colonial era, the fountains of Kolkata have not only added a certain charm and elegance to the city’s landscape but have also been significant sources of water supply and contributors to public sanitation.

Lionhead Water Fountains

Long before public water fountains were introduced to Kolkata, the holy Ganga (which was being polluted by uncontrolled human activity), was the only source of water for drinking and bathing.

In the 1870s, the British set up a series of fountains to supply clean, drinking water. Originally manufactured by Alley & MacLellan, a Glasgow (Scotland) based engineering company, the fountains were imported to India. Inspired by Greco-Roman motifs, their design comprised a pillar-like structure cast in iron with a spout projecting out of a lion’s head.

A system of pipelines connected the Hooghly, a tributary of the Ganga, to different areas of the city after passing through an upflow/downflow gravel filtration process.

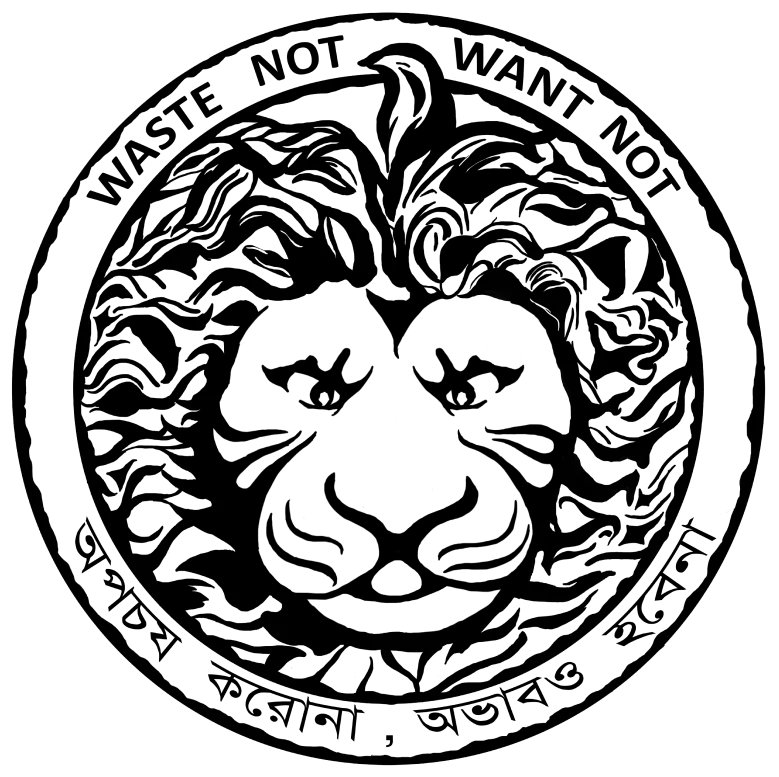

“The British wrote an imperial decree that said, “Waste Not, Want Not” and in some cases the same in Bengali that read: “আপচয় করোনা, অভবো হোবেনা” to dispel these tales and avoid the wastage of water.”

Water outlets to/from these pipelines are still used today in various parts of the city for domestic purposes and remind us of the relationship that exists between the river, the city, and its people. Today, most of the spouts lie broken while the water supply pipes remain. The latter functions independently adjoining the fountains or are haphazardly connected to the mouth of the lionhead due to a lack of workmanship.

The presence of the lionhead fountains demonstrated the British government’s concern for hygiene. An imperial decree that said “Waste Not, Want Not” was engraved on the fountains to mitigate water wastage. However, they were not without controversy. Some social groups opposed their presence claiming that the tap washers were made of cow or pig skin, insulting several religious sensibilities. Others believed that the water from the lion’s mouth was not as holy as Ganga water. To dispel these rumours, the same decree was engraved in Bengali and read: “আপচয় করোনা, অভবো হোবেনা” (Opochoy Korona, Obhab o Hobena) alongside a logo of the Calcutta Water Works (CWW).

These lionheads contributed to the aesthetic character of the then colonial capital, blending in with the architectural styles of the buildings and monuments alongside the riverfront.

Lionhead Fountains in Different Parts of the City in Current Times

“Back in the days, urban planning was very systematic water fountains were designed in a way that for every few hundred yards they would also have the provision of fire water systems. Although damaged, this is one of them still standing at Jorasanko, Kolkata”

Panioty Fountain

Installed in 1898, this marble drinking water fountain can still be found in the northwest corner of Curzon Park/Surendra Nath Banerjee Park, now known as the Bhasha Udyan. The fountain was commissioned by Lord Curzon in memory of Demetrius Panioty, who belonged to a family of Greek traders and became an assistant private secretary to several Governor Generals of India.

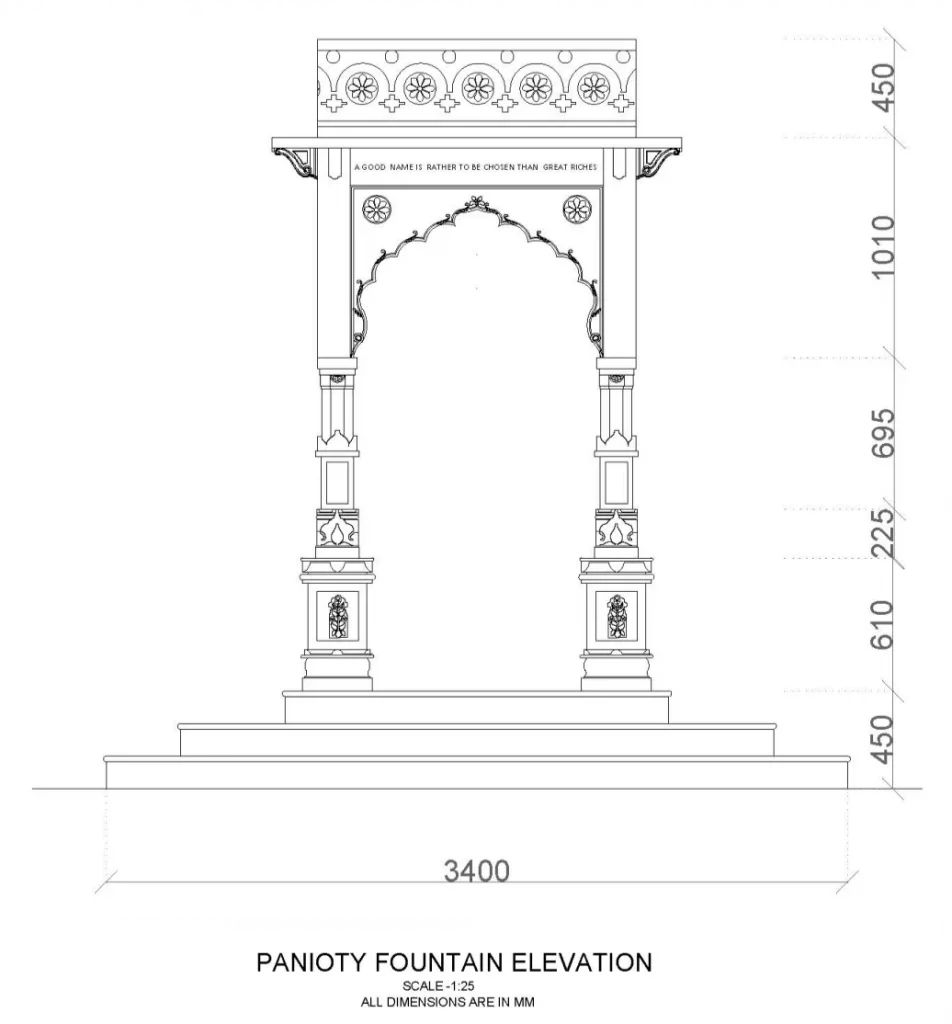

The fountain is built in the form of a Mughal pavilion with nine-foiled cusped arches with beautiful motifs on each of the four columns. The western arch of the monument is engraved with a proverb from the Bible that reads “A good name is rather to be chosen than great riches.”

Interestingly, this monument served as a prominent backdrop in Parash Pathar (The Philosopher’s Stone) a 1958 film by renowned auteur Satyajit Ray. It is here that the protagonist, played by Tulsi Chakraborty, finds the titular stone.

Years of negligence have left the fountain in a sorry state. There is a significant amount of structural damage, signs of organic growth, and vandalism on its various surfaces. The surrounding area has seen an overgrowth of unkempt vegetation and untrimmed trees, lending the fountain vulnerable during storms which are a frequent occurrence in the city. On the other hand, it has been listed as a Grade I heritage structure in the list of Heritage Buildings of Kolkata, developed by the Kolkata Municipal Corporation.

“The Panioty Fountain is a marble drinking water fountain installed in 1898 at the junction of Old Court House Street and Esplanade Row, in memory of Demetrius Panioty.”

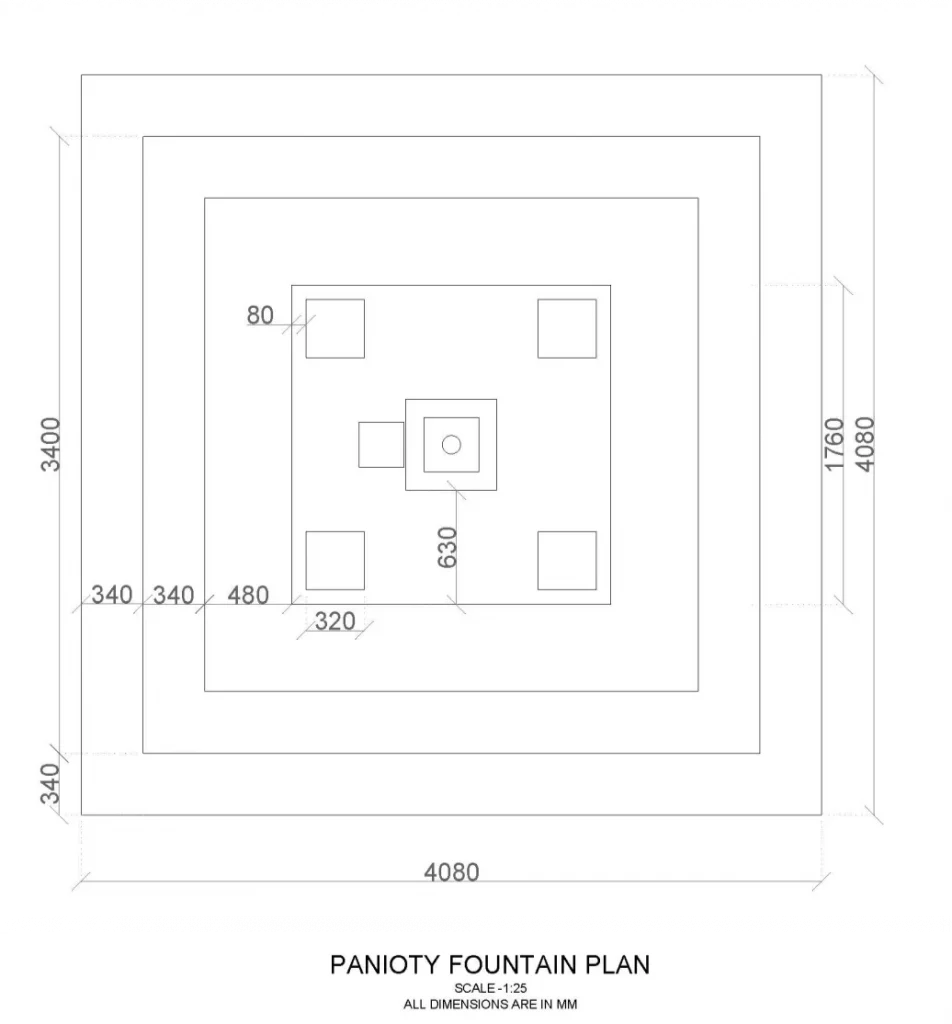

Measured Drawings of the Panioty Fountain – Gangotri Ganguly, Arindam Roy

Panioty Fountain as seen in Ray’s ‘Parashpathar’

A 3D Model Walkthrough of the Panioty Fountain

Panioty Fountain 360 images

McDonnell Fountain

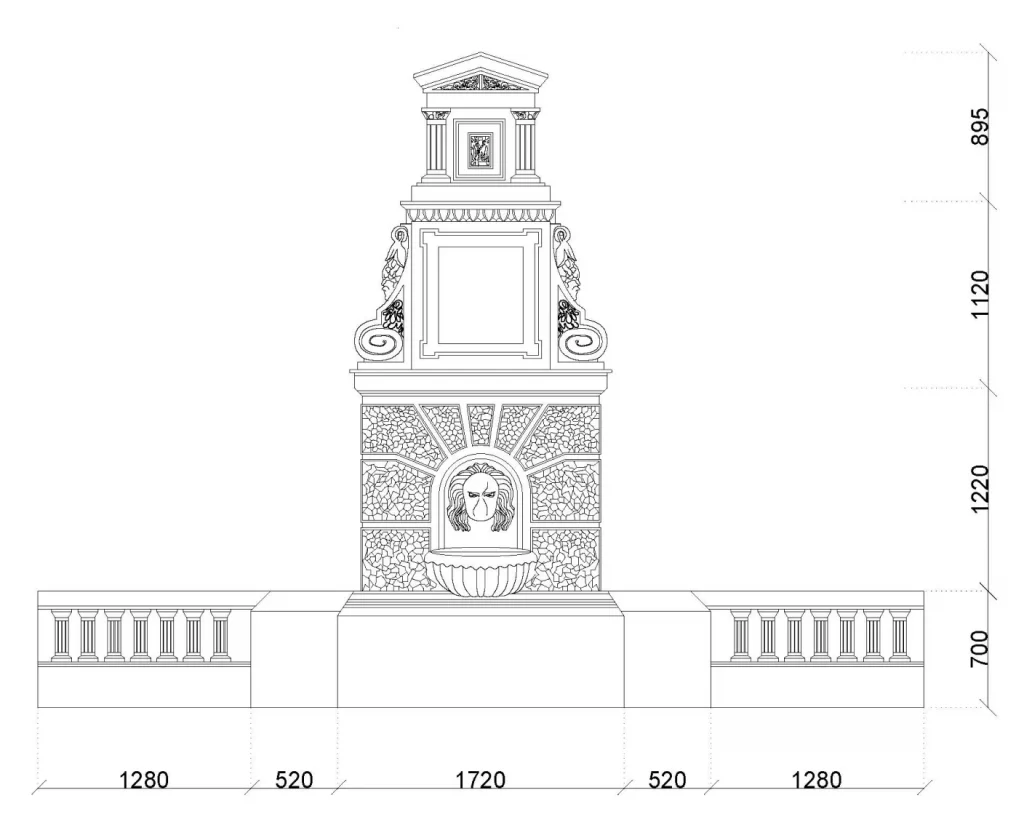

“The fountain is a fine example of Gothic revivalist style, with a floral capitol on its apex and a lion’s head on the front facade.”

This is a Victorian-styled water fountain located near the Calcutta High Court on Esplanade Row. It was built in 1894 as a memorial to William Fraser McDonnell by his English friends. McDonnell was a senior member of the Bengal Civil Service and a judge of the high court. The fountain is a fine example of Gothic revivalist style, with a floral capitol on its apex and a lion’s head on the front facade. The fountain also had a cistern of water for horses as McDonnell was a steward of the Calcutta Turf Club, the then premier horse racing club in the subcontinent.

An inscription of 1850 on one side and 1886 on the other marks McDonnell’s tenure as a civil servant in Bengal unlike other memorials which acknowledge the year of birth and death. The fountain was once both a functional and beautiful feature but has fallen into disrepair over time. It currently has no direct access since it is surrounded by railings and is hidden behind rows of parked cars and clothes that are hung on the railing to dry. The inscription that once boasted McDonnell’s achievement on the white marble plaque has faded and shows evidence of severe damage while the lionhead lies broken and dry. Although the cistern for the horses is now absent, the fountain stands as a reminder of Kolkata’s colonial heritage and the philanthropy behind the provision of public drinking water fountains.

The Forgotten Fountain by Desmond Doig

Measured Drawings of the McDonnel Fountain

McDonnel Fountain 360 images

References

- Chandra, S. (2015). PANIOTY FOUNTAIN … British Acclaim for Greek Legacy. Retrieved from panioty-fountain-british-acclaim-for.html

- Datta, R. (2014). McDonell Monument, Calcutta (Kolkata). Retrieved from mcdonnell-monument-forgotten-drinking-fountain/

- GetBengal. (2021). Panioty, Kolkata’s marble drinking water fountain by the Greeks! Retrieved from panioty-kolkatas-marble-drinking-water-fountain-by-the-greeks

- Ghosh, D. (2014). The McDonnell Drinking Fountain: A Forgotten Monument of Calcutta. Retrieved from the-mcdonnell-drinking-fountain.html

- Gupta, D. (2021). The Greco-Roman lion taps are still found on the streets of Kolkata. Retrieved from https://www.getbengal.com/details/the-greco-roman-lion-taps-are-still-found-on-the-streets-of-kolkata

- Ray, S. (Director). (1958). Parash Pathar [Motion Picture]. Retrieved from Video

- Sengupta, S. (2021). McDonnell Fountain at Dalhousie Square: A gem gathering dust. MyKolkata. Kolkata. Retrieved from Article

- Tathagata Neogy, Immersive Trails.