East Kolkata Wetlands is the largest sewage-fed wetlands in the world, and a Ramsar site, sustained by the collective practices of the peri-urban wetland community who see wastewater as a nutrient to be preserved as it enhances livelihood opportunities. With this mindset, they judiciously use waste water engaging an elaborate set of management practices to perpetuate their livelihood security.

Apart from perpetuating livelihood practices the local women utilise easily available date palm leaves and weave them into mats. Jaggery making from the date palm tree is also a common practice during winters. Needless to mention that the community is subject to a variety of threats from rampant illegal wetland filling, encroachment and development plans; poor maintenance of wastewater canals and such is causing production failure and is leading to an economic crisis and unemployment.

Wetland Community

At the East Kolkata Wetlands, the city sewage is organically treated through symbiotic relationships between algae and bacteria in the presence of sunlight with the help of community practices like fish farming, vegetable growing, paddy cultivation and animal husbandry. Thus, the trifecta of food producing, treating sewage and assisting drainage along with the rich existing biodiversity, sustain the ecological balance of Kolkata.

Biodiversity in EKW

“By its very nature, the East Kolkata Wetlands is a living archive, a museum that transcends static forms.”

The biodiversity at EKW boasts a robust family of 93 plant species, 123 kinds of birds, 79 varieties of fish, 10 kinds of amphibians, 29 reptiles, 24 crustaceans, and 13 species of mammals have been recorded from these wetlands thus far. Children from the above-mentioned schools have been working to catalog and build an archive of the plethora of diverse flora-fauna of EKW through on-ground research, secondary data collection and various artistic methods like drawing, painting, mural making and other media types like photographs, poems, songs, dance and skits. By its very nature, the East Kolkata Wetlands is a living archive, a museum that transcends static forms. The archive exists not only in the form of accessible data but is co-owned and co-authored by all the participants involved in the process. Participation ensues from the local school children to their guardians, teachers, family,friends, neighbours – thus reaching the entire wetland community.

Nature Explorers’ Lab

Besides making an inventory of the flora-fauna that thrive in the region, Disappearing Dialogues (dD) is extensively working with the EKW community to understand the correlation in the existing biodiversity. Collaboration with ecology experts, young artists, illustrators and art therapists where students from various schools took part in a nature explorers’ lab helped pave the way for a mutual learning experience.For dD, it has been noteworthy to witness the gradual realization of local youngsters (mostly first generation learners) making the connections between their lived surroundings and newly acquired information and knowledge.

A Nature’s Diary

The youngsters have become sharp observers and take note of every new species and enthusiastically share with us. They are the best archivists of the EKW, fully aware of their locale and able to narrate the story of their own community. They have been recording various species of kingfishers, egrets, cormorants along with common birds such as bulbul, barbet, myna, drongo etc. through art and poetry. Insects found range from bugs, beetles, butterflies, worms, dragonflies, damselflies, etc – the most interesting being the prishtotan poka (water strider) which walks on water.

Other than the different variants of the palm tree, shojne (drumstick), shobeda (sapodilla), shirish (albizia lebbeck), kathal (jackfruit), nona/aata (custard apple) and aam (mango) are the most prevalent trees of EKW.

The diversity in EKW is vast in terms of plant species that grow on land and water. Some are edible while many have medicinal value. Taro, a leafy green that is found abundantly, is probably the most popular and dynamic vegetable in EKW. Not only are there various types of taro, both edible and wild, but also about a dozen recipes that are cooked on a daily basis in households. While some spice it up with shrimps, or make a paste of it, others may boil, mash and add a dash of lemon to their taste. Some common fish in EKW are koi (climbing perch), lyalentika (nilotica), puti (pool barb), cyprus, various types of carp and others.

Students have also engaged in cooking sessions based on the wetland environment. One of the most important functions of EKW has been food production – fruits, vegetables, paddy and fish. A variety of leafy vegetables such as kalmi saag (water spinach), notey saag (green amaranth), hinche saag (buffalo spinach), kulekhara (marsh barbel) are local to the wetlands. The community besides growing these also use them as part of their regular consumption. As an added feature, recipe stories by children described and documented the process of cooking that is a daily activity in most homes. Another interesting activity initiated has been Season Watch – understanding the cyclical nature of seasons and how trees, shrubs, weeds undergo changes through the year.

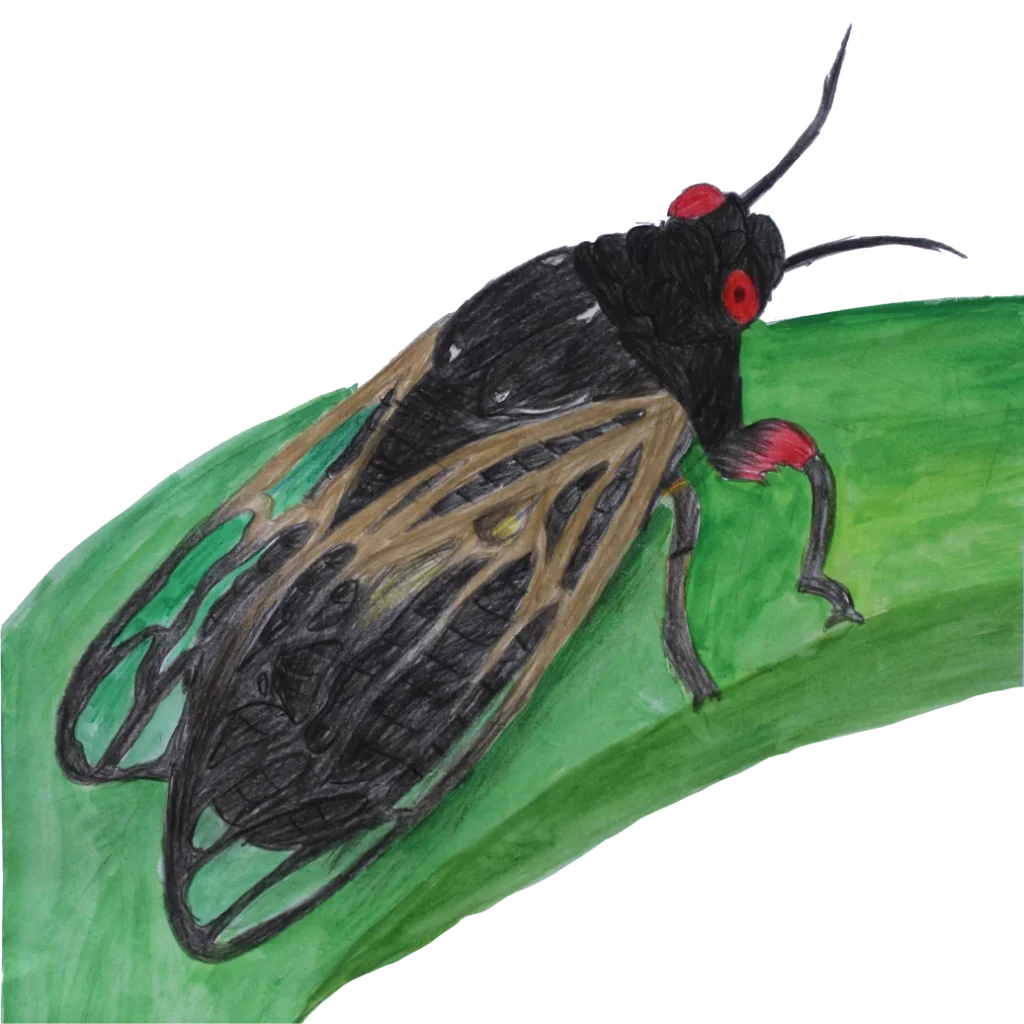

Cicada

Referred to as Uchhingre in Bengali, cicadas are jumping insects. Their hops are very swift, fast and about 10 cms long. They have compound eyes and are found almost everywhere.

Panburi

Panburi is a wild plant found mostly near the banks of wetlands. It has medicinal properties.

Blue-throated Barbet

Barbets are of different kinds but this one can be mostly spotted during spring. For the same, its Bengali name is Boshonto Bouri. The bird specifically perches on trees that have fresh leaves.

Dragonfly

Dragonflies are mostly summer visitors at the wetlands. Similar to them are damselflies, shorter in size. It is said they were one of the first winged insects to evolve, some 300 million years ago.

Waterhen

Waterhens are very commonly seen in EKW often spotted at a proximal distance from humans. They dig holes near water bodies and prefer to stay inside them.

Silver Carp

These fishes grow up to 60-100 cm with a maximum length of 140 cm and weight of 50 kg. They are very silvery in colour and have very tiny scales on the body but there head is scaleless.

Wetland Stewards

Dd has observed that building elementary research approaches and processes for students to observe minute details within their immediate surroundings and document data through visual and textual details thus bridging art and science together has been a liberating and empowering exercise. Additionally, creating this living archive resource centre has generated exponential value for this unique ecosystem.