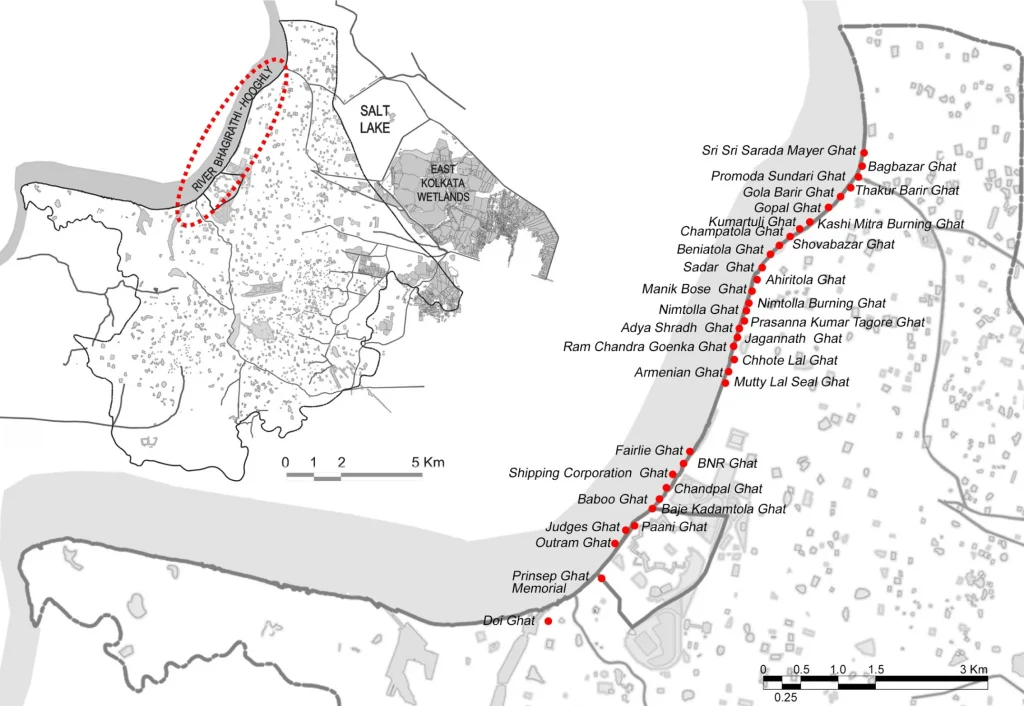

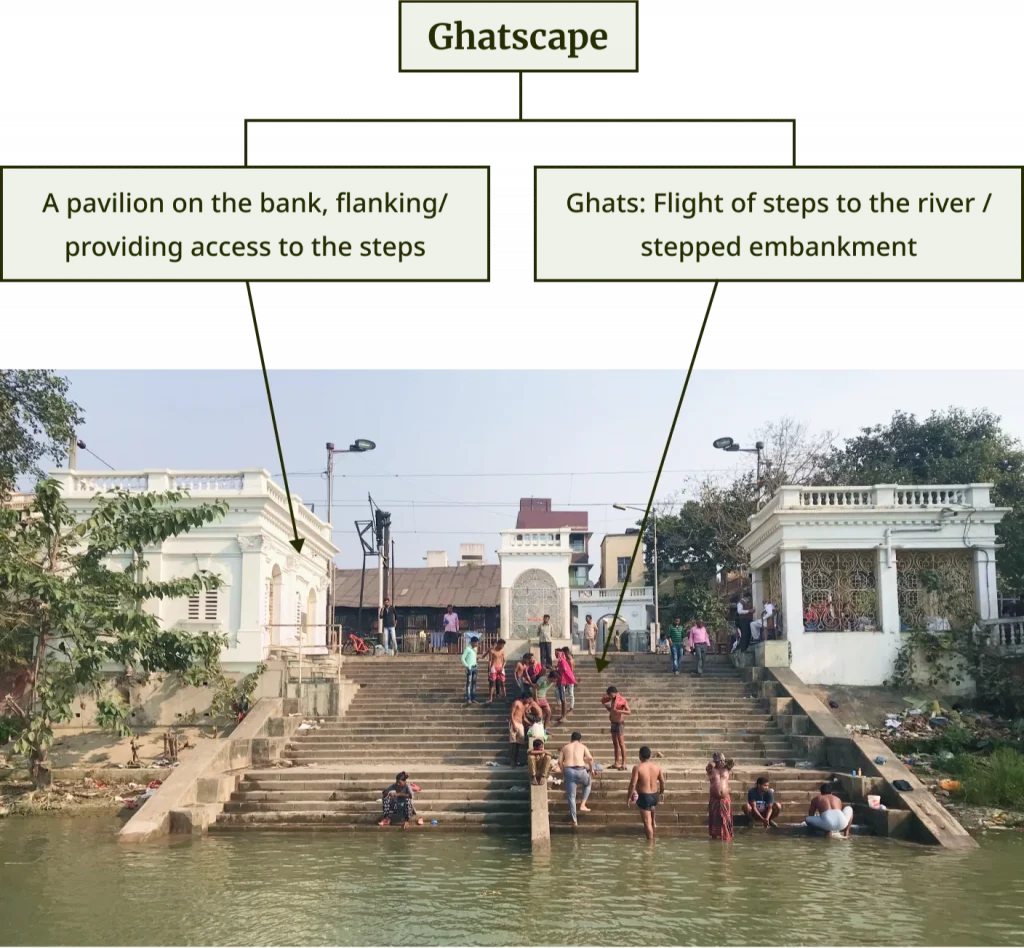

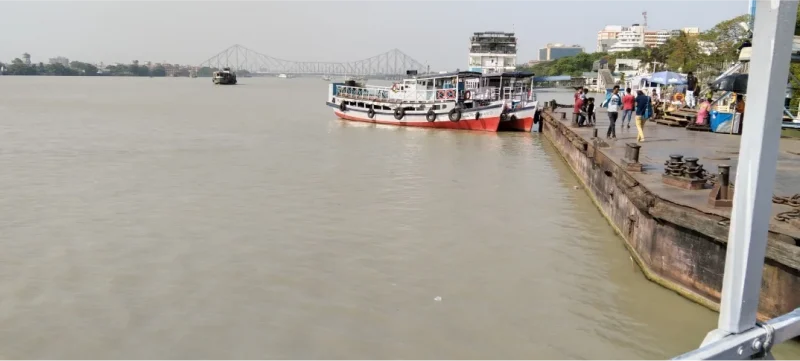

The 40 ghats and ghat pavilions along the sacred Ganga River, locally known as Bhagirathi-Hooghly, flowing adjacent to the western edge of Kolkata, form the focal point of this narrative. By highlighting this Ghatscape, we emphasize its cultural and ecological qualities, as well as the contemporary urban challenges it confronts. Ghats, in the context of rivers refer to flights of stairs that descend into the water from the surrounding temples and/or pavilions. They provide access for drinking and holy bathing, and are unique features representing the consistently symbiotic relationship between rivers and settlements over centuries. This Ghatscape, with its layers of geographic, geomorphic, hydrological, and ecological milieus (not to mention the religious and socio-cultural elements) are ubiquitous along most sacred rivers in India. The ghats along the Bhagirathi-Hooghly have given Kolkata a distinguished identity, supporting diverse social, recreational, transportation, and industrial activities.

Little Europe on the Ganga

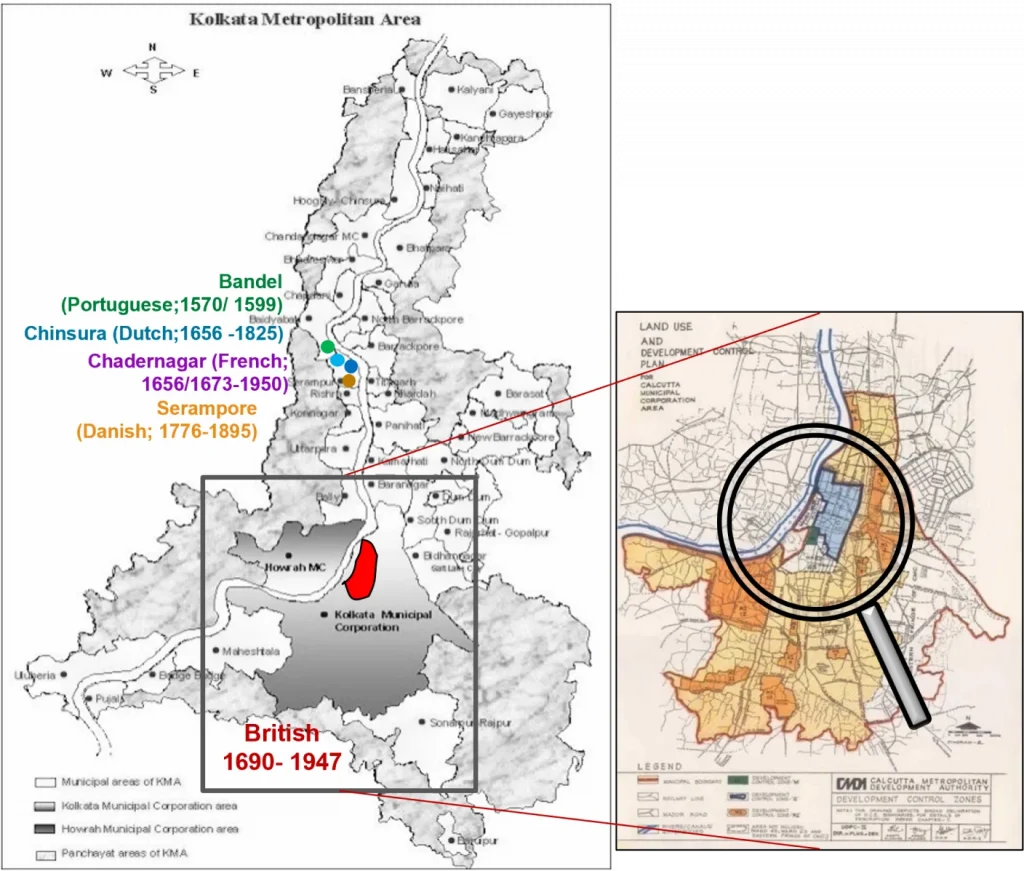

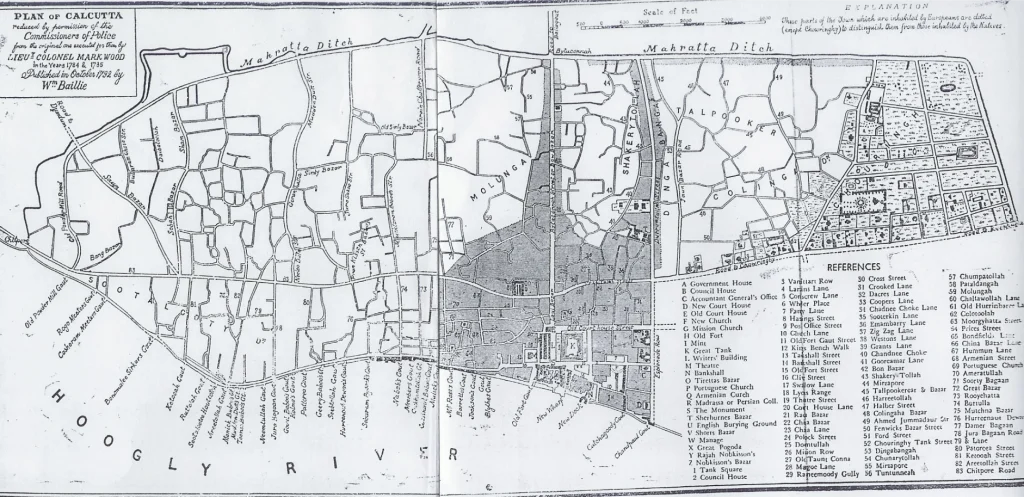

India’s centuries long tryst with European colonisers has been well documented. Maritime trade ( of products such as spices, cotton, and even indentured labour) with several colonial nations and others across the globe, meant that numerous port cities throughout the country became colonial strongholds. During the 16th and 17th centuries, colonisers focused their attention on a swampy, densely forested region in the lower Gangetic delta which became Calcutta, now Kolkata.

There was a conflict between nations who traded with India by land, such as the Turks and the Armenians, and maritime traders, such as the Western Europeans, which shaped the development of the city and of West Bengal. The Dutch, Portuguese, Danes, and the French set up footholds on the western bank of the river, while the British seized the region closer to Kolkata which became a seat of power. Given its strategic location as a popular port city, the city was home to people from across the world, thus commencing its role as India’s “cultural capital” in addition to being the capital of British India.

The ghat pavilions exhibit an eclectic form of ghat architecture, with varying materials, designs, and functions. According to the classification of the UNESCO World Heritage Committee, the entire Ghatscape can be classified as an “associative cultural landscape” due to its cultural and sacral association with the river, presenting a unique historic urban fabric that connects people, places, culture, and faith. Since most functions, structures, and original characteristics have remained largely unchanged for over 60 years, the Ghatscape qualifies as a Historic Cultural Landscape (HCL).

Ghatscape Components

The Bhagirathi-Hooghly riverfront in Kolkata is dotted with ghats as well as ghat-associated pavilions, both constituting the unique ghatscape of Kolkata.

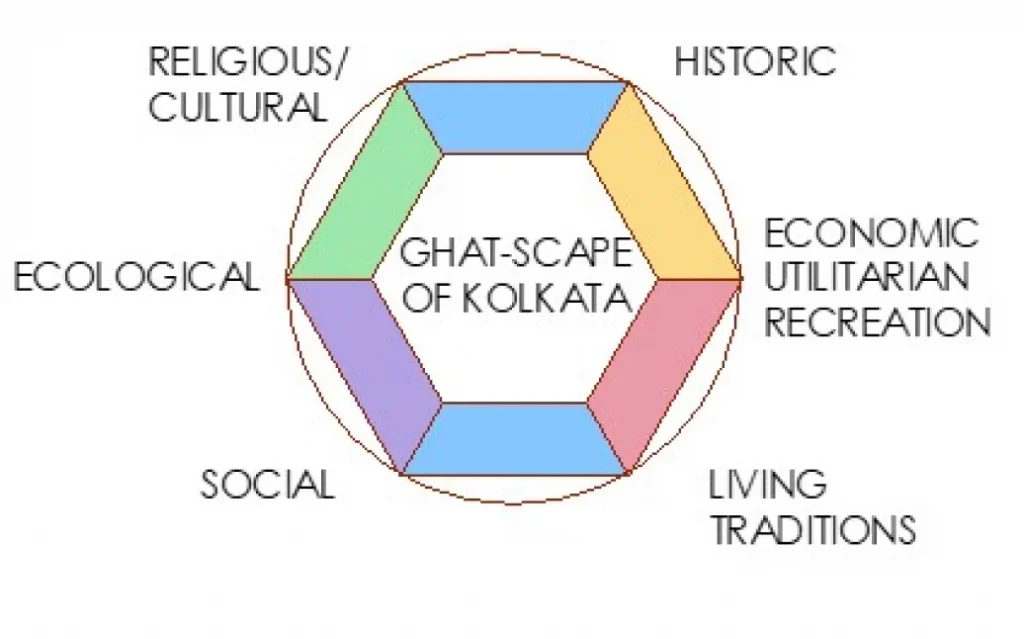

Dimensions of the Ghatscape

Life in the Ghatscape

The river and the ghatscape offer a glimpse into the socio-economic and cultural character of the community.

Ghatscape through Drifts and Decades

The ghat-pavilions were commissioned mainly by prominent personalities of the time, different ethnic groups, businesses, or trade organizations, and were named after their patrons.

Then

Now

Then

Now

Chhotelal Ghat ki Ghat – 1875 (PC: Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland (RCAHMS) 1912-14) ; 2019 (Source: 2023, Sukrit Sen)

Then

Now

Ram Chandra Goenka zenana Bathing ghat – 1890 (source: Old Indian Photos) ;

2021 (Source: 2023, Sukrit Sen)

Then

Now

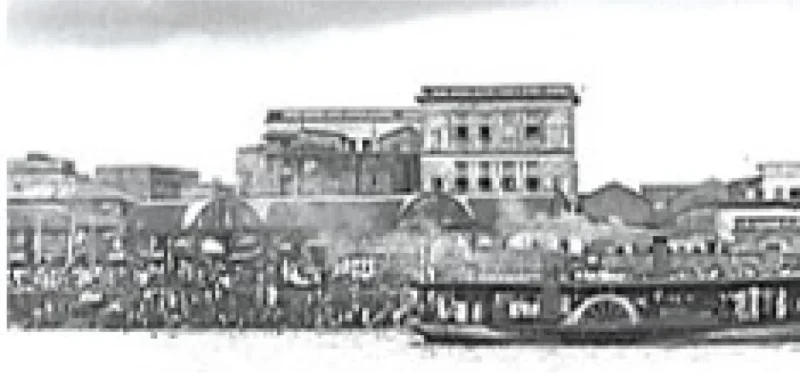

Chand Pal Ghat – 1770 (painting by James Baillie Fraser, 1826) ;

2023 (Wikipedia Commons)

Then

Now

Jagannath ghat – late 19th c. (source: Wikimedia Commons) ;

(Source: 2023, Sukrit Sen)

Then

Now

Mallick ghat -1855/ 1874 (source: Wikimedia Commons/ Bourne and Shepherd, c.1880’s) ;

2023 (Source: 2023, Sukrit Sen)

Then

Now

Ahiritola ghat – late 19th c. (source: Wikimedia Commons) ;

2023 (Source: 2023, Sukrit Sen)

Then

Now

Babu Raj Chandra Das ghat or Babughat – 1830 (adjacent to Chand pal ghat) (source: noisebreak.com) ; 2019 (source: http://double-dolphin.blogspot.com )

The Ghatscape through the Decades

Originally, the ghat pavilions were named after their patrons who were usually people with some political and cultural influence in the city.

People, Events, Associations, and Memories

The Ghatscape holds a collection of cultural narratives that bear witness to numerous pivotal moments in the city’s history. The growth and subsequent decline of the ghats intertwine with the evolution of the riverfront and the development of the city. These ghat functions provide a glimpse into the socio-cultural and economic scenarios of erstwhile Calcutta and its affluent citizens, also known as Babus.

Mayer Ghat

“This is the northernmost ghat after the Bagbazar canal and was frequented by Sri Sri Ma i.e., Holy Mother SaradaMoni Devi for her daily bath during her stay at Mother’s House, Bagbazar between 1909 to 1920 till her mahasamadhi. The route taken by her is indicated on the map. Previously known as Durga Charan Mukherjee Ghat, it was renamed as ‘Mayer Ghat’ in her honour.”

This is the northernmost ghat after the Bagbazar canal and was frequented by Sri Sri Ma i.e., Holy Mother SaradaMoni Devi for her daily bath during her stay at Mother’s House, Bagbazar between 1909 to 1920 till her mahasamadhi. The route taken by her is indicated on the map. Previously known as Durga Charan Mukherjee Ghat, it was renamed as ‘Mayer Ghat’ in her honour.

Mayer Ghat is also a success story in rejuvenating the ghat area, restoring the historic pavilion, and the environment. Steered by the local community, it was led by the Ramakrishna Math, Bagbazar in 2004. Designed by the Architecture Department at JU, the scheme was implemented with active participation of all public stakeholders—KMC, Eastern Railways, Kolkata Port Trust (KoPT), Kolkata Police, Calcutta Electric Supply Corporation (CESC), and local members of parliament and members of legislative assembly.

Chhotelal ki Ghat

“The stone is dedicated by a few English women to the memory of those pilgrims, mostly women, who perished with Sir John Lawrence in the cyclone of 25th May 1887”

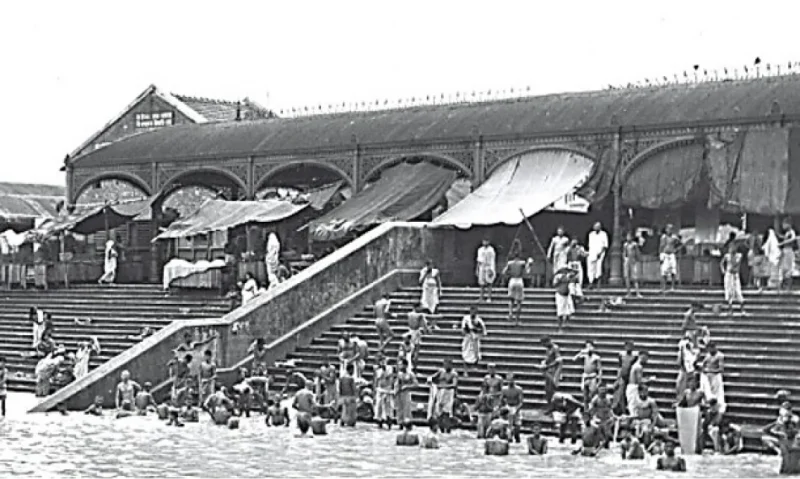

Designed by British architect, Richard Roskell Bayne in1875, Chhotelal ki ghat remains the most photographed ghat pavilion and an iconic landmark. Several plaques marking historic events, including a tragic event, adorn its walls.

The absence of a railway line to the Puri Jagannath Dham in the late 19th Century, forced many pilgrims (mostly women) to make their journeys via the river. A steamship, the Sir John Lawrence by McLine and Co., voyaging from Calcutta to Chandbali, Orissa was a popular, and perhaps the only, passage on this route. On May 25, 1887, the cyclone caused the steamship to capsize with all the passengers on board.The plaque reads, “The stone is dedicated by a few English women to the memory of those pilgrims, mostly women, who perished with Sir John Lawrence in the cyclone of 25th May 1887.”

Courtesy: British Library

(PC: Sarthak Paul, 2023)

Ghats—Gateways and Transport Terminals to Erstwhile Calcutta

Chand Paul Ghat

Named after Chandra Nath Pal, the keeper of a shop at the ghat, the Chandpal Ghat has been around since 1774 on the southern boundary of the then Dihi Calcutta (Ray, 1902).

With the new Fort William set to come up in 1781 and the jungles in the area in-between cleared, the ghat became the landing place for everyone from British Governor Generals, Commanders-in-Chief, Judges, and Bishops including Sir William Jones in 1783 and James Prinsep in 1819. It was also from this ghat that Sri Aurobindo sailed to Pondicherry by the French ship SS Dupleix (Sri Aurobindo Institute).

Babughat

Babughat and its pavilion was constructed in memory of Babu Raj Chandra Das by his wife, Rani Rasmoni in 1830. It was the most commonly used river port at the time. On 30th December 1841, Mother M. Delphine Hart and 11 Loreto nuns from Ireland landed at Babughat. Bishop Carew welcomed them to Calcutta and Loreto House, the first Loreto school in India, was established at 5, Middleton Row on 10th January 1842 by the Sisters.

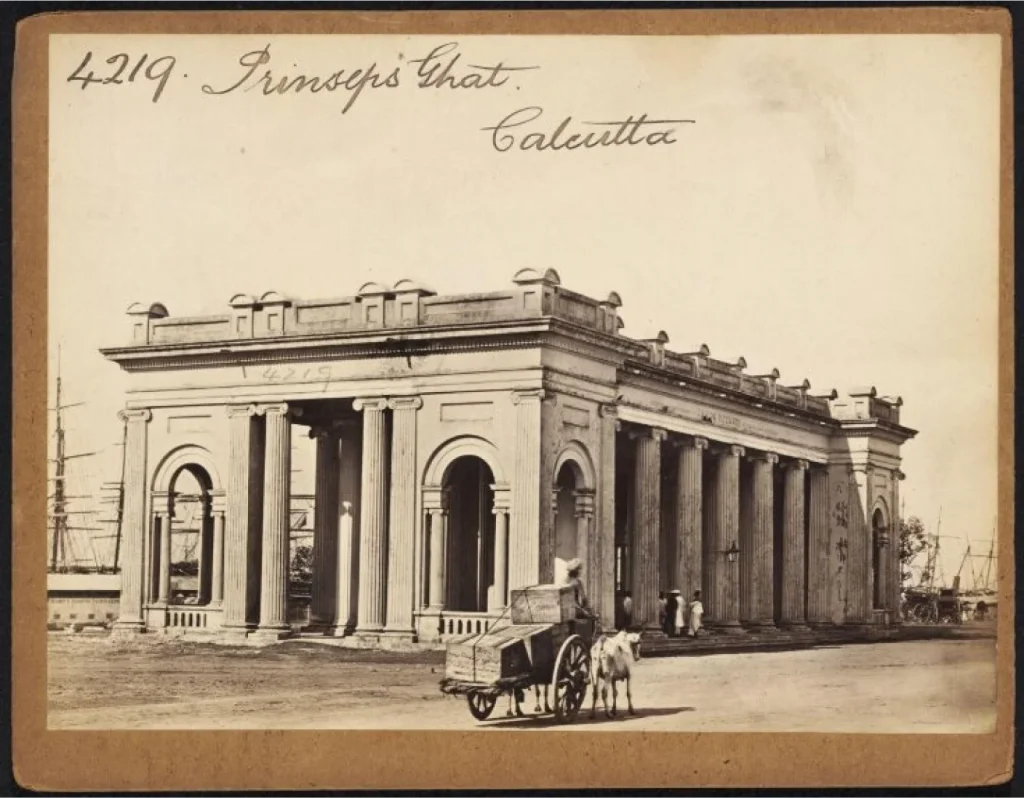

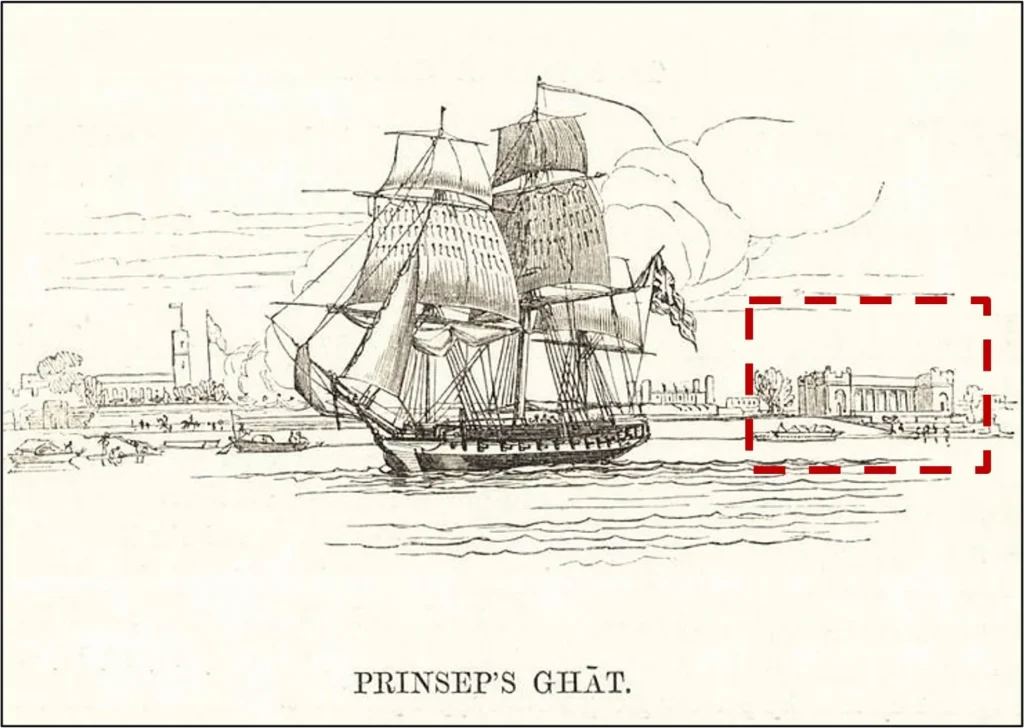

Prinsep Ghat

This memorial ghat structure, completed in 1843, was a tribute to James Prinsep (1799-1840), an eminent scholar, orientalist, and antiquary. The architecturally elegant ghat–pavilion became the preferred landing place for British dignitaries as long as the sea-river transport were/was? in use. It witnessed the arrival of Albert Edward, Prince of Wales, the eldest son of Queen Victoria in 1875. The future King George V in 1905, and the British royal family in 1911. Currently, the memorial pavilion sits 100 metres inland from the riverbank.

360 Virtual Tour of the Princep Ghat

Juxtaposition of Form and Style

The ghat–pavilions are a testament to the diverse architectural styles that reflect Kolkata’s cultural affluence. Ghat construction activities spread over a span of nearly 200 years display a diverse array of design and structural forms.

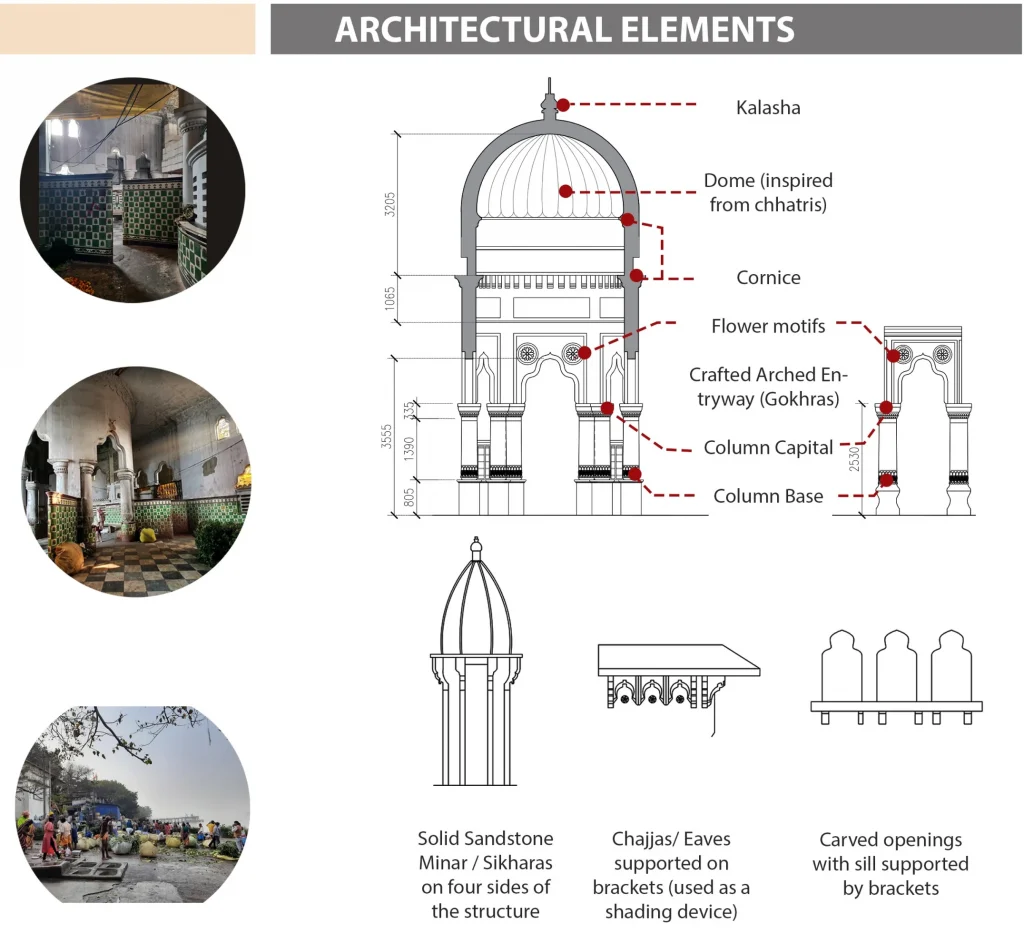

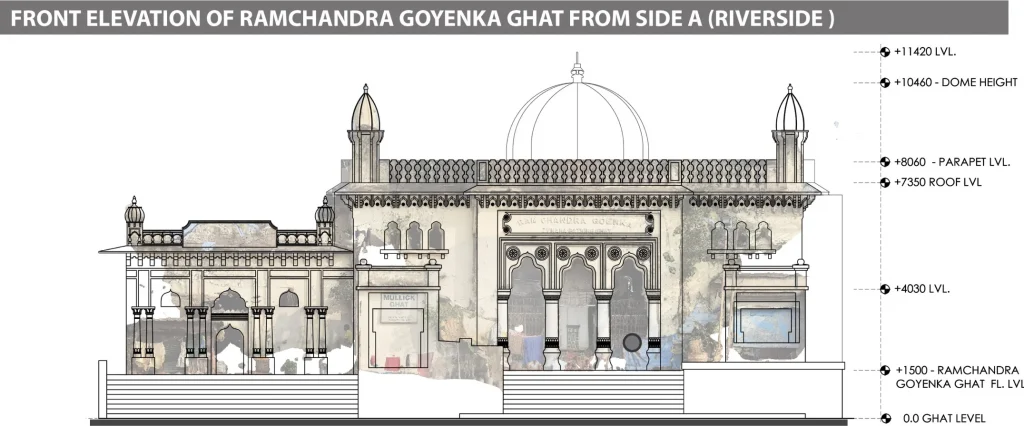

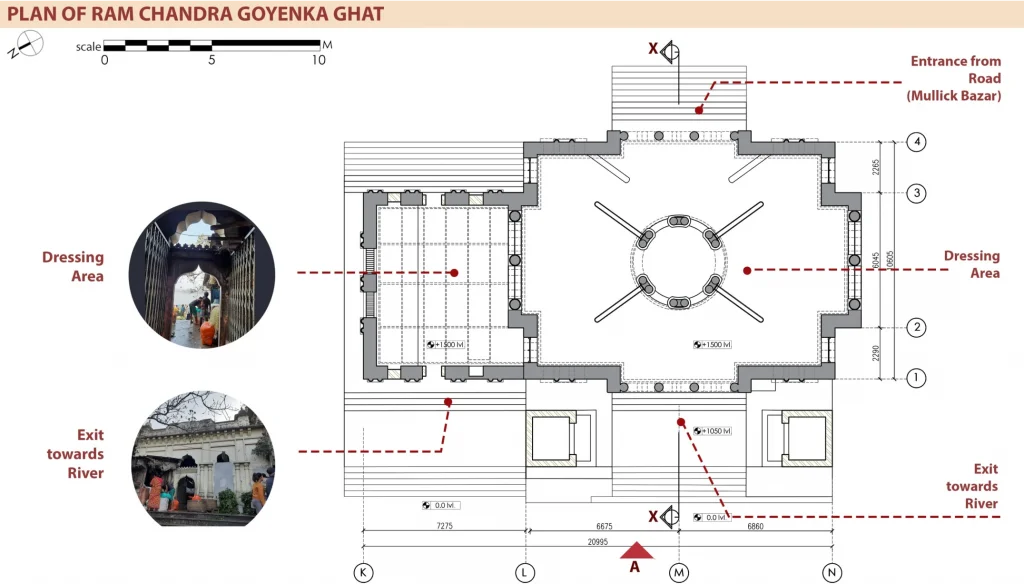

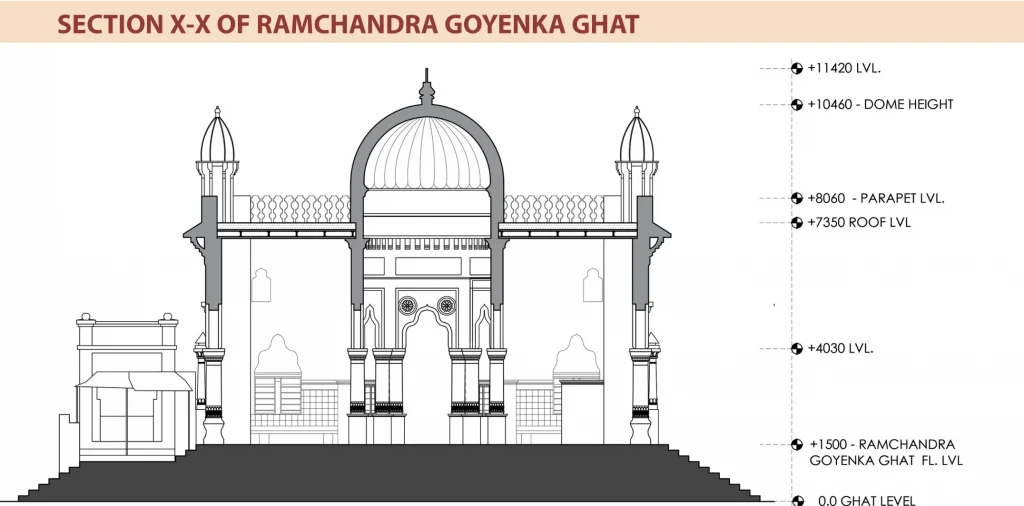

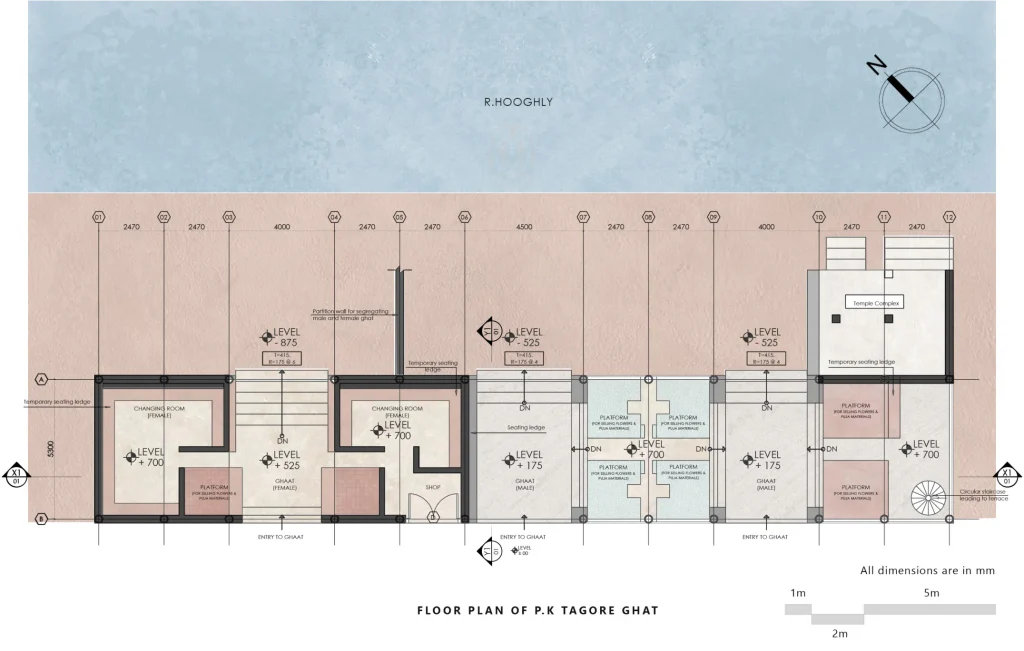

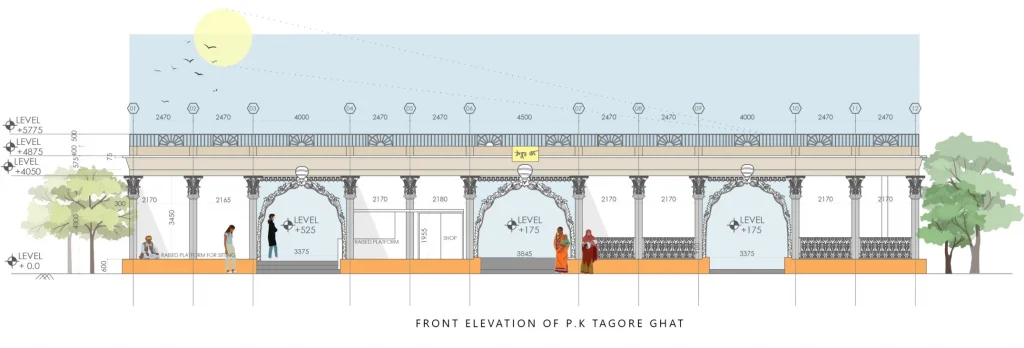

Babughat with pediments supported by Doric columns, and Prinsep Ghat Memoria with Ionic columns, follow distinct European architectural styles. Kumartuli Ghat, Nimtala Ghat, Champatala Ghat, and Adya Shraddha Ghat are mostly square-shaped masonry structures with elements of Indian architecture. Some pavilions like Jagannath Ghat and the P.K. Tagore ghat are cast-iron structures. The iconic Chhotelal ki Ghat presents impressive elevations with stately Corinthian columns, arches, and a raised central drum that was obscured due to a vertical expansion in the late 1980s. Ram Chandra Goenka Zenana Bathing Ghat (1890), is a grand structure, albeit in a mixed architectural style, with graceful arches, a central dome, and chhatri-like turrets at the four roof corners. Mutty Lall Seal Ghat Pavilion (1840) seems like it was much ahead of its time, with tall arched openings and flat-roof entablature held by imposing Corinthian columns.

Zenana Ghat 360 Tour

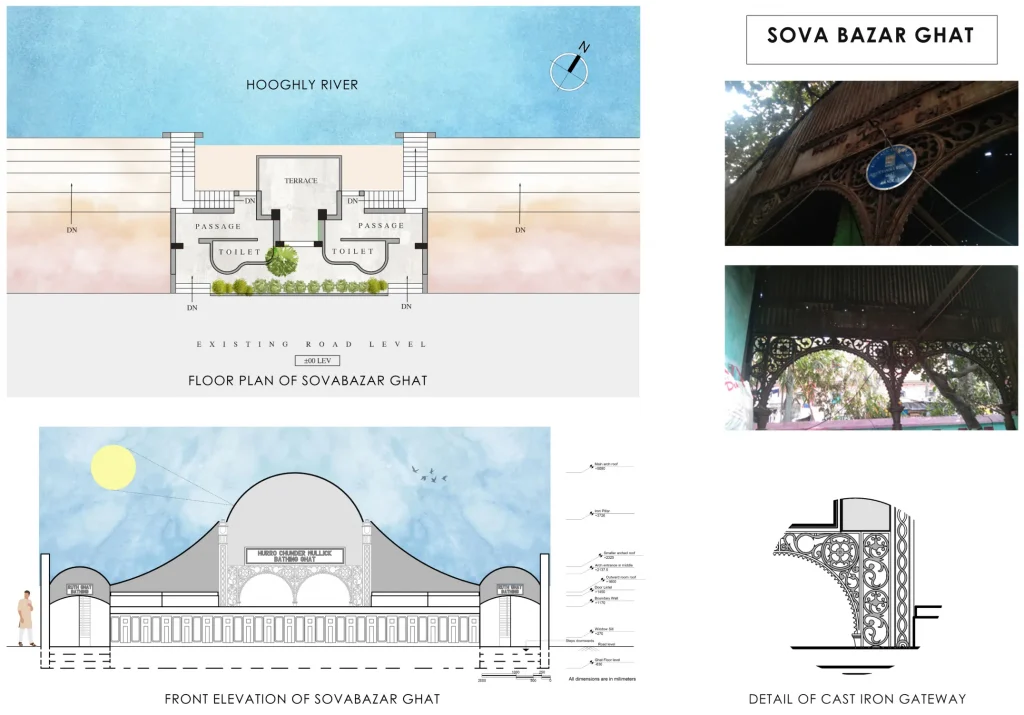

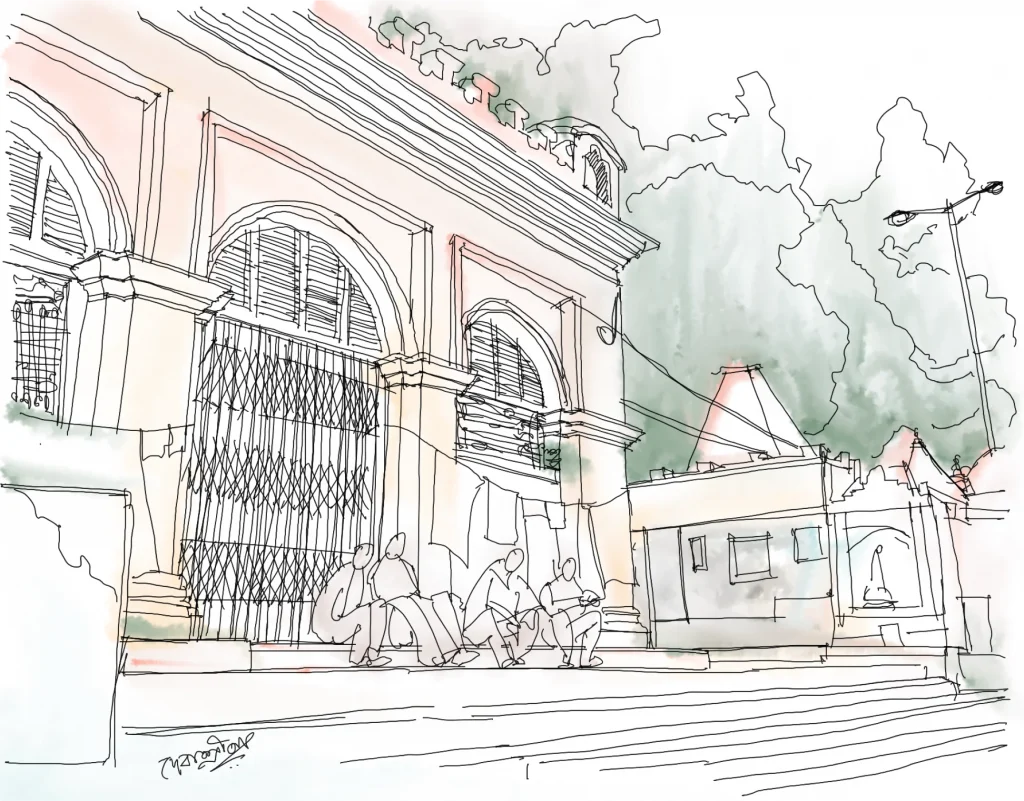

(Drawn by – Debashrita Kundu)

P K Tagore Ghat 360 Tour

Hurro Mullick Ghat 360 Tour

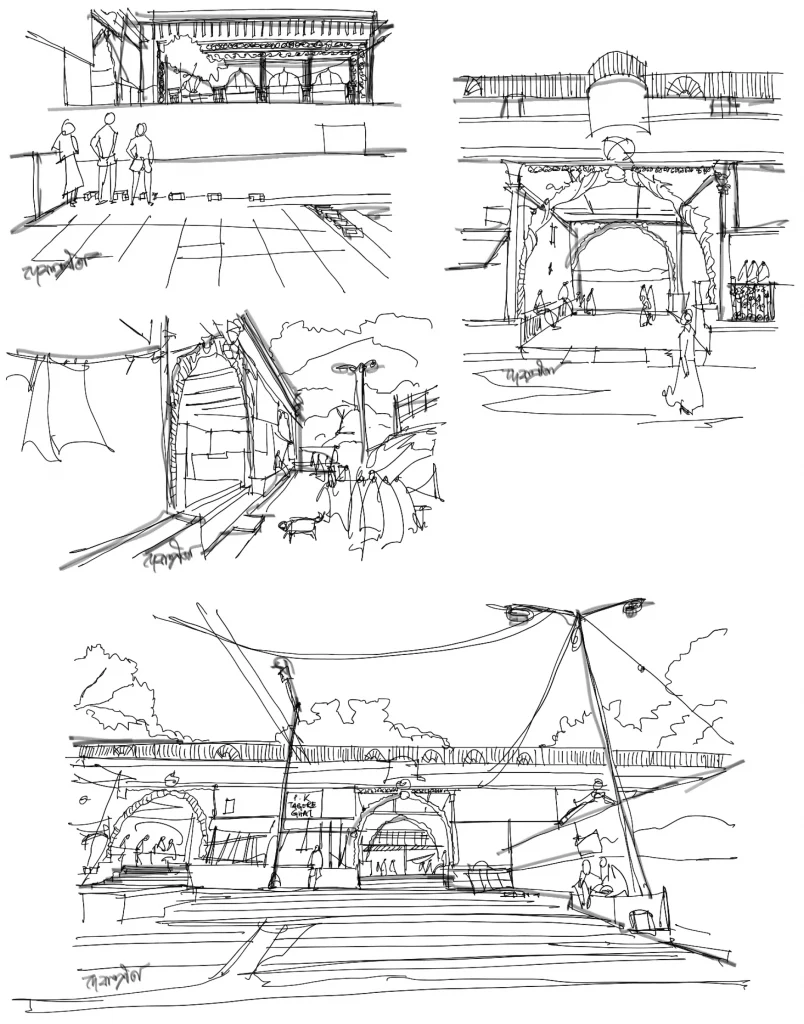

Sketches

Current Challenges

The ghat-pavilions, with their splendid architecture, have lost much of their relevance today. Once standing as grand gateways, they are now relegated to the backyard, as is the river. Although their use for holy bathing and as ferry terminals continues, the cultural and recreational values are all but lost. Even though most of these ghat-pavilions are declared Grade I heritage structures, they have fallen victim to encroachments, vehicle parking, night shelter, and commercial activities. The Circular Railway corridor adds to these woes by fragmenting the riverfront. Environmental issues like plastic pollution of the ghats and river-front further aggravate the complexities.

We imagine a riverfront that is accessible to all and which, punctuated by these unique ghat–pavilions will narrate the story of a three-hundred-year-old city, its layered history, its triumphs and tragedies, its people and palaces, its class systems, and its immensely significant role in the Indian Independence movement.

Mayer Ghat and Prinsep Ghat give us hope that other ghat-pavilions can be restored, their old glory revived, and the adjacent areas developed as hubs of recreational and cultural activities, sensitive to the River Hooghly and the natural environment.

References

- Bardhan, S. and Paul, S. (2023), The cultural landscape of the Bhagirathi-Hooghly riverfront in Kolkata, India: studies on its built and natural heritage, Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development, Vol. 13 No. 2, pp. 219-237. The cultural landscape of the Bhagirathi-Hooghly riverfront in Kolkata, India: studies on its built and natural heritage | Emerald Insight

- Bardhan, S. and Paul, S. (2019), Envisioning an eco-cultural urban landscape Studies on the Ghats of the River Bhagirathi-Hooghly in Kolkata, India, IFLA CL WG’s International Symposium on Historic Cultural Landscapes: Succession, Sustenance and Sustainability, Seoul, 18-20 Nov. 2019.

- Bardhan, S. (2006). Riverfront rejuvenation: ‘Mayer Ghat’ in North Calcutta. Journal of Indian Institute of Architects, 71(8). pp. 43.

- Jadavpur University. 2003-04. Study & Documentation of Ghat Structures Along Calcutta Riverfront – A Study conducted by students of Department. of Architecture, Jadavpur University, Kolkata. Unpublished.

- Kundu, A.K. and Nag, P. (1996), Atlas of the City of Calcutta and its environs, National Atlas & Thematic Mapping Organisation (NATMO).

- Mitra, R. and Mitra, R. ‘Saswata Kolkata’ Part I- ‘Gangar Ghat’

- Motilal, A. Howrah – Kolkatar Gangar Ghat’.

- Mukhopadhyay, A. (2018), “MullickGhat and the Jagannath steamer ghat”, available at: MULLICK GHAT AND THE JAGANNATH STEAMER GHAT – PURONOKOLKATA(accessed 29 December 2020).

- Mukhopadhyay, H (1915), Kalikata Shekaler O Ekaler. Kalikata Sekaler O Ekaler – Harisadhan Mukhopadhyay / কলিকাতা সেকালের ও একালের – হরিসাধন মুখোপাধ্যায় : Bangla Rare Books : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive

- Old Indian photos (accessed April 2023), Various Riverside Ghats of Calcutta (Kolkata) – c1912-14 – Old Indian Photos

- Ray, A.K. (1902), Census of India, 1901, Vol. VII- Calcutta, Town and suburbs, Part-I, A short history of Calcutta, Bengal Secretariat Press, Calcutta.

- Sri Aurobindo Institute (accessed May 2023), Departure to Pondicherry – Sri Aurobindo (1906-1910)