‘A city with a soul’—this is how Kolkata has been described over the years in Bengali literature. But this soul doesn’t just reside in palatial buildings or picturesque avenues, it is on the busy streets, electric trams, traditional handicrafts, and certainly in the water. We often forget that the things we take for granted in our daily lives came about because of a series of inflection points in history.

Civic Duties in the East India Company

In the early years of the Company’s rule there was no civic government in Kolkata; the Mayor’s court, established in 1726, held exclusive judicial powers.

Municipal services were neither relevant nor significant at the time, but change was afoot, and the Company took on some of the more pressing civic responsibilities to attract people to the fledgling metropolis. The tenure of Governor General Wellesley was a crucial turning point when public works became an essential component of the local government’s obligation. His “Minutes of June 16, 1803” is a historical document that shows the government’s first concerted efforts for the orderly growth of Kolkata.

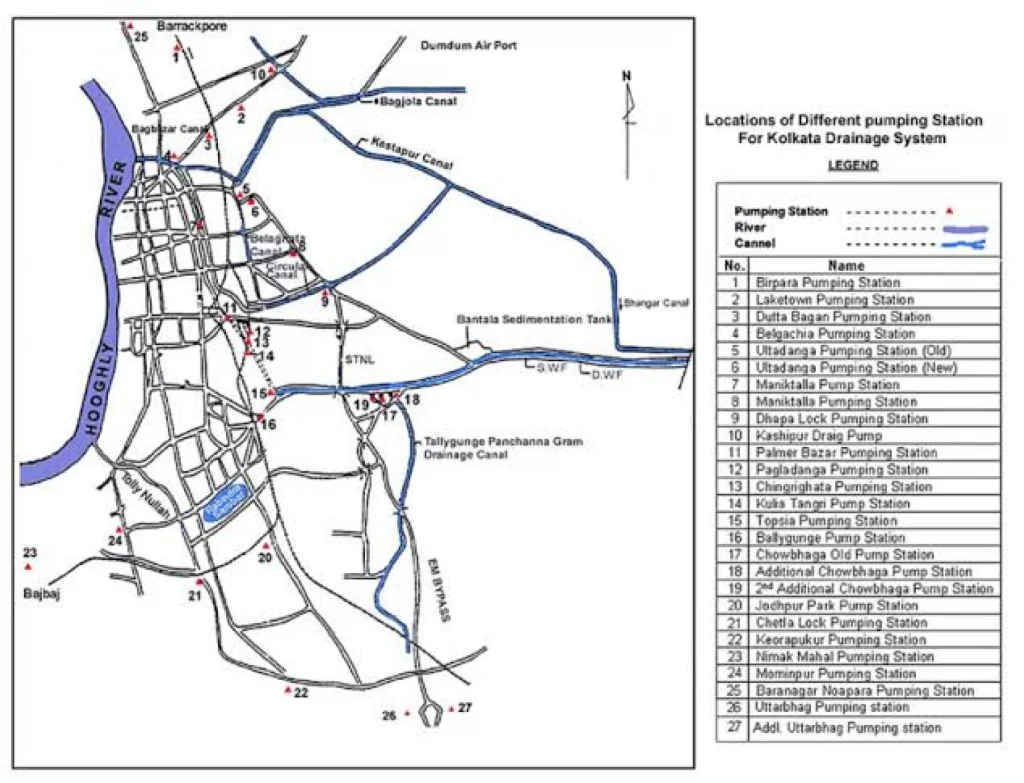

Some officials at the time seemed quite concerned with the existing infrastructure, or lack thereof, in the city. Therefore, in 1807, the Superintendent General of Police suggested using a lottery system to bring in more money for municipal improvement. A committee to see to this process was finally formed in 1817. Additionally, in a plan to introduce public infrastructure to the city, emphasis was placed on building a primary sewage system as well as repairing and building new roadways. Frequent flooding occurred during spring tides when the water levels of the Hooghly River rose and inundated the town’s Esplanade and converted the neighborhood of DumDum into a temporary water body. The government also drew attention to the fact that the woodland belt of the Sundarbans was being steadily cleared away by human activity, affecting the natural protection it offered against sea water.

“In 1807, the Superintendent General of Police suggested using a lottery system to bring in more money for municipal improvement.”

Development through Social Awareness

“In 1832, a considerable sum of money (Rs 3341.8) was spent on drainage in parts of the city connecting the neighborhoods of Bowbazar, Durrumtollah , Cositollah, and Wellington Square.”

After much thought to infrastructure, public health was given top priority by both the imperial government and the municipal administrators during the urban expansion of Calcutta. As a result, administrators in the 1830’s sought to shape the colonial capital city into a “sanitary city ” by invoking theories of hygiene and sanitation on the one hand and of civilization and improvement on the other.

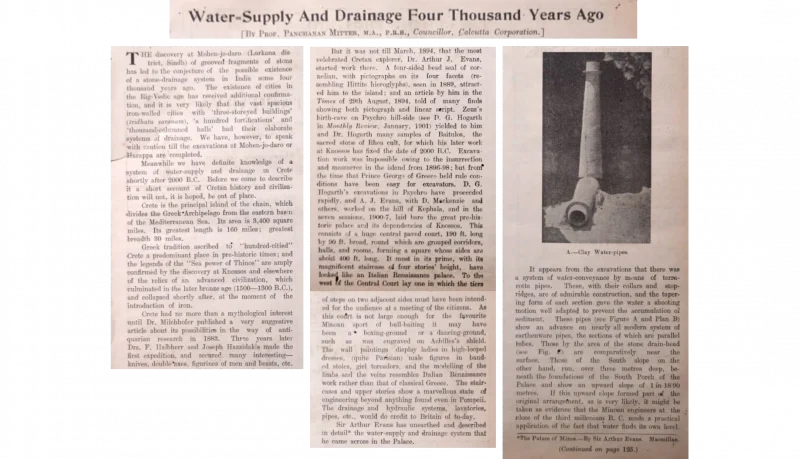

In 1832, a considerable sum of money (Rs 3341.8) was spent on drainage in parts of the city connecting the neighborhoods of Bowbazar, Durrumtollah , Cositollah, and Wellington Square. Governor General Auckland established the general committee of fever hospitals and municipal improvements in 1838 to further enhance hygienic conditions and public health. Dr. Martin, a surgeon at the local hospital in Durrumtollah, was the driving factor behind this significant accomplishment. The committee sought advice from prominent Bengalis such Raja Kali Krishna Bahadur, Dr. Madhusundar Gupto, and Dwaraka Nath Tagore. The city’s requirements and the conditions at the time were carefully examined by the fever hospital committee and came to the swift decision that an underground drainage system was the only workable solution. Most of the committee’s expert witnesses agreed but there was a hunch that a constant flow of water through the sewers, unless mechanically pumped (at too high a cost), would make a sewerage system ineffective and far too dangerous to fix. There were several plans put forth, but the committee chose to investigate the Captain Forbes Scheme. He advised making salt lakes a crucial component of the city’s drainage system and to build an aqueduct made of stone that would connect the Hooghly under the Old Chitpur Bridge to the Old Park Street Cemetery and the Salt Lakes using a large, open canal that would run nearly parallel to the Entally Canal. Besides drainage, it was believed that the proposed canal would also provide a cheap and simpler form of navigation and a source of income for the community.

Challenges and Innovations

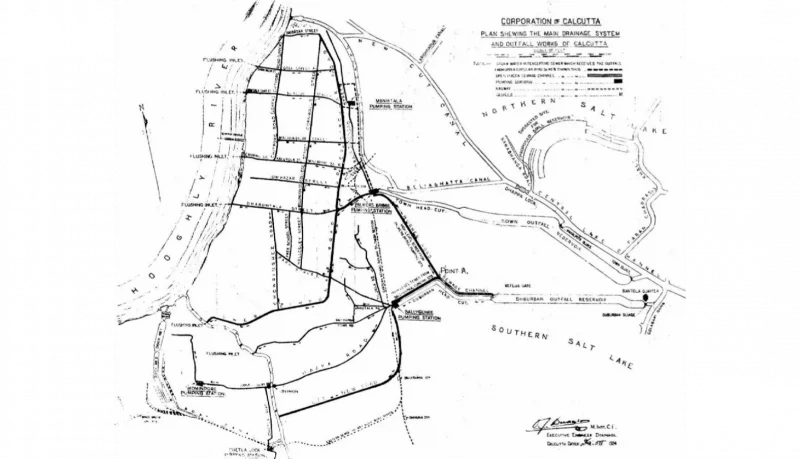

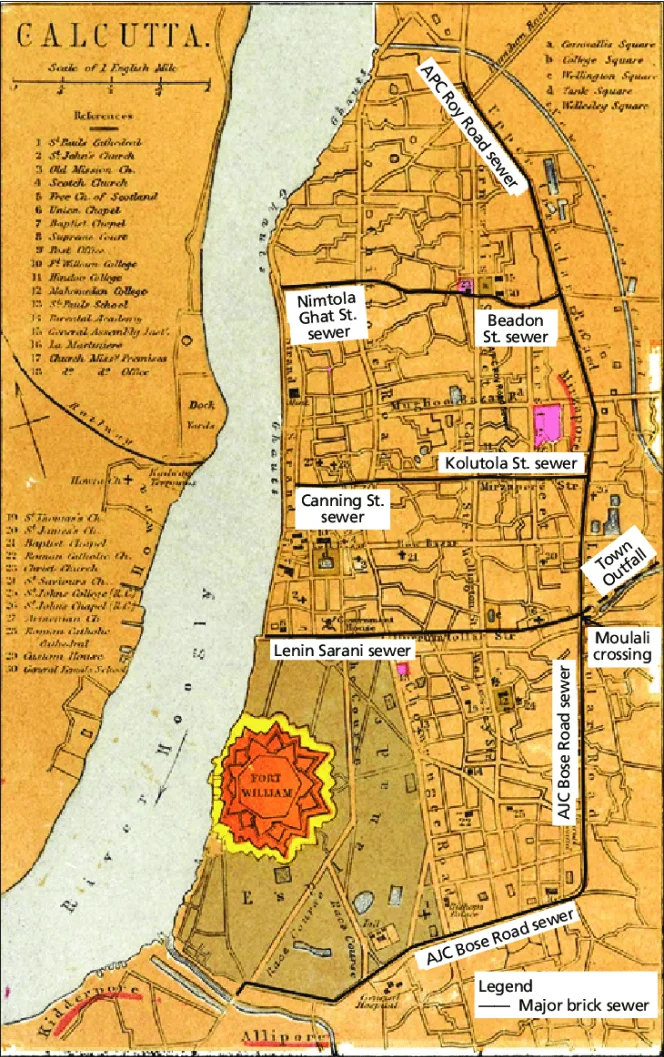

Many recommendations over the years failed to materialize due to a lack of institutional support. Surface sewers were installed across Kolkata by 1857, but the hygiene and sanitation concerns in the city were only growing. A “combined system” for the removal of both storm water and sewerage, or “dry weather flow” was created. The system’s foundation was first suggested in 1855 and approved in 1859 with construction taking place between 1860 and 1875. Under the city’s main streets, a large, 8 feet tall by 6 feet wide sewer was built that connected to smaller subterranean cross sewers. It was designed by William Clark, the East India Company’s former head engineer. It took 16 years to complete Clarke’s model and the result was a series of pipe sewers (4.8 km in brick and 59.2 km in stone).

In the early 20th century the Suburban Improvement Committee wanted to extend the drainage and sewerage to the suburbs and appointed chief engineer Mr. J. Kimber. In 1909 a combined sewerage system was designed for the Kidderpore and dock areas.

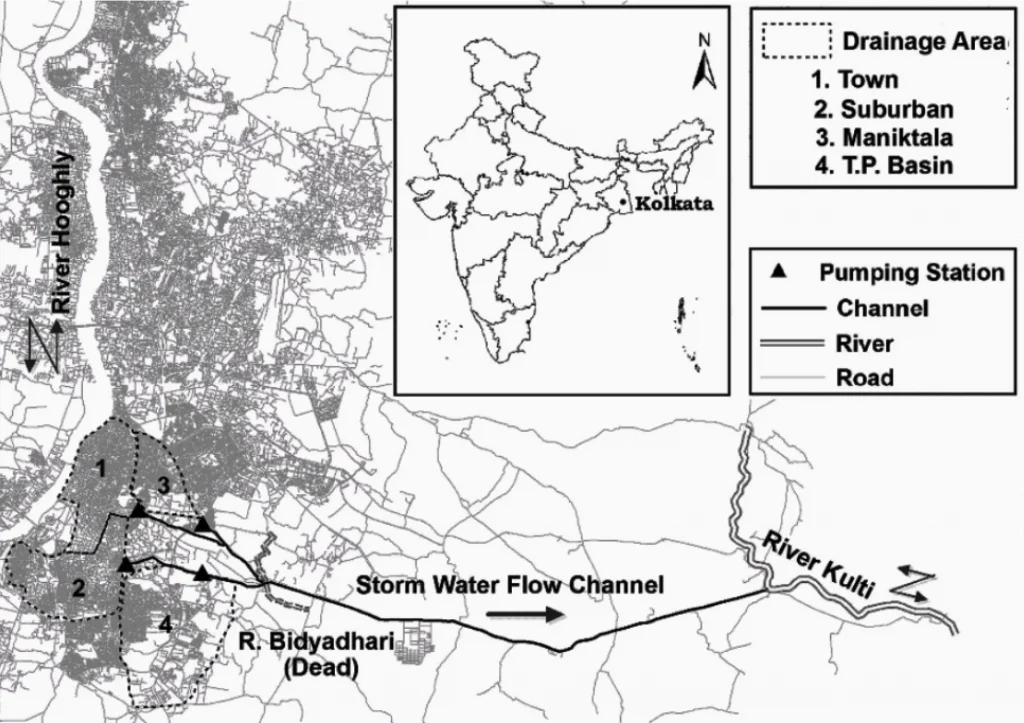

Over the years, several changes were made to tackle the crisis which emerged with the deterioration and over silting of the Bidyadhari River (which was kept for the outfall and lost its significance due to the declining condition of the Yamuna River which fed it). Alternative paths were created under the leadership of Dr. B.N. De, a distinguished engineer from the Calcutta Corporation, towards Kulti Gunge under the renowned Kulti Outfall Scheme. This scheme not only improved the productivity of the system as a whole but also distributed the outfall systematically.

Did you know?

- It was decided that to protect the population of Kolkata and its suburbs, a circular bund or embankment was erected beyond the inhabited part of the suburbs and along the edge of the salt lake and other swamps. A comparative study of the physical feature of Kolkata and Amsterdam was made and a proposal was placed for the consideration of the high court that “much advantage would be gained if the superintendent engineer were directed to proceed to Holland, for the purpose of inspecting embankments in that country, accompanied by two or three young men who have qualified for the engineers . The two countries are similar in every respect and the plans adopted by Dutch with success to protect Amsterdam and whole Holland from the encroachment of the sea cannot but prove most useful to our engineers in Bengal” (Judicial, 9th Jan 1943, No. 8)

- Along with roads, bridges were also constructed to ensure improved communication. In 1801 a new bridge was built in Allypore. One of the most important bridges was built over Tolly’s Nullah in 1822 and named in honor of the Marquess of Hastings. The first iron bridge in India, a foot bridge, was erected in 1822 over Tolly’s Nullah at Kalighat .

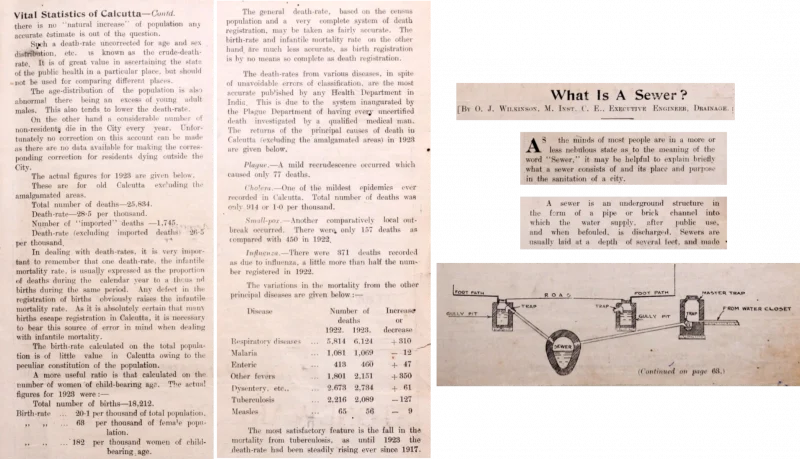

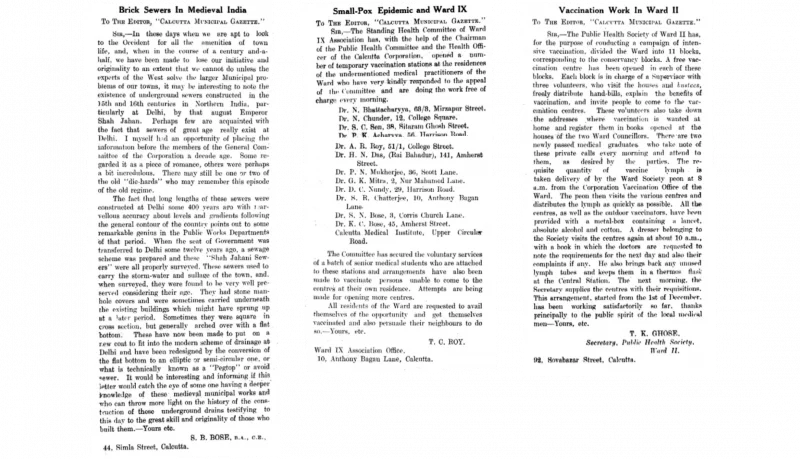

Excerpts from initial days of sewer design methodologies in Kolkata

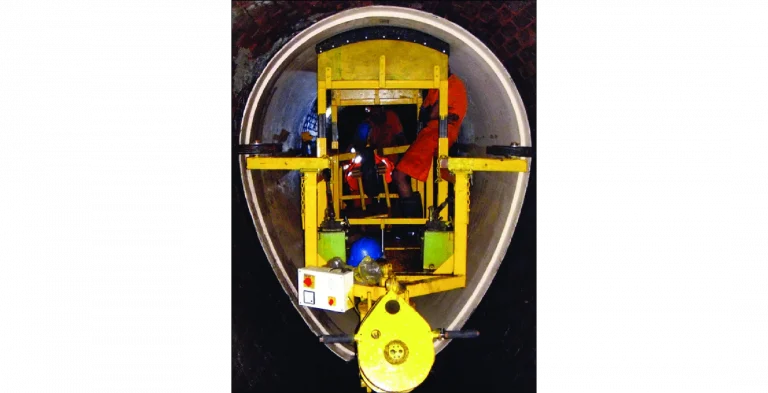

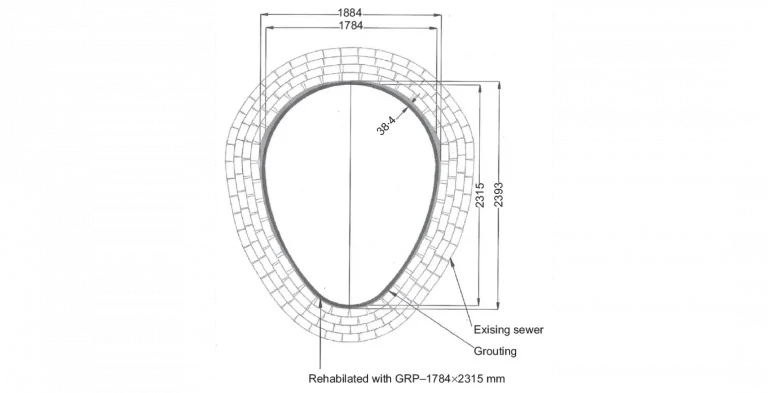

Cross-sectional views of Kolkata’s historic sewers

“The drainage system of Kolkata is one of the oldest organized sewage systems in the country. Although the population of the city has grown considerably, the drainage system continues to meet the needs of 1.5 million citizens. While it may not comprise the most effective apparatus, particularly during the monsoons, it is witness to rapid urbanization that threatens its status as a historical marvel. ”

The Sewers of Kolkata- The story of its rejuvenation

References

- Selected documents on Calcutta 1800- 1900 , Directorate of state archives, Higher education Department government of west Bengal.

- Calcutta municipal gazette November 22nd , 1924

- Calcutta municipal gazette November 28th , 1925

- Calcutta municipal gazette 1948

- Calcutta municipal gazette 3rd January, 1925

- Sunil Kumar Murmu, Nazimul Islam and Dhubojyoti Sen (2021) : the heritage sewer networks of Kolkata (Calcutta) and ascertaining their coping potential under growing urban pressures, ISH journal of Hydraulic Engineering.

- Link to this article: read here

- Link to medium article

Acknowledgement

I would like to express my profound gratitude to Directorate of state archives, west Bengal and Kolkata Municipal Archives, West Bengal for allowing me to access the documents and maps available on drainage system of Kolkata

I would also like to extend my sincere gratitude to the list of people without whose guidance and expertise this work would have been incomplete:

- Jenia Mukherjee ( faculty in humanities and social sciences, IIT Kharagpur )

- Dipanakar Ganguly ( Kolkata Municipal Archives)

- Ranajit Das ( Kolkata Municipal Archive )

- Debagni Mitra ( visual artist )